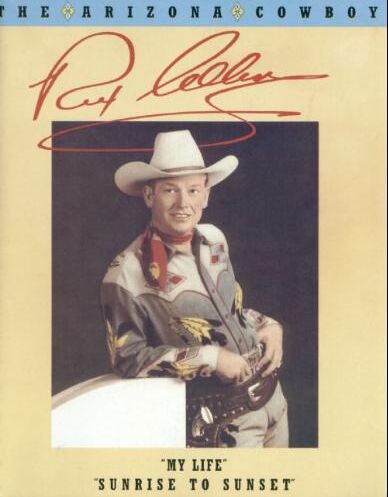

My Life: Sunrise to Sunset

Rex Allen with Paula Simpson Witt and Snuff Garrett (1989)

My mother had seen a movie with cowboy star Rex Bell, who was married to Clara Bow, the silent screen star. Mom just fell in love with him, and so she wanted to name me Rex. That's how I became Rex Elvie Allen. My dad called me Elvie growing up. So, I was Elvie in Willcox, and most of the people in Willcox didn't know my first name was Rex. A lot of them thought I had changed it after I left town. But I just decided I wanted to use my first name. Elvie is a lousy name for show business. Later along comes a kid with a worse name—"Elvis." Maybe I should have kept mine. (2)

I lost one of my little sisters when we lived up there. Her name was Mildred. She was just a few months old when she died of what they called summer complaint. I guess just stomach trouble. Milk didn't agree with her or something. I remember the funeral to this day.

We also lost my brother Wayne out there when I was about five. He was two years older than me. Wayne and I were out in the field helping my mom hoe weeds out of the beans. We had a canteen out there, and my dad was working in the next field with a team of mules, cultivating some corn. We ran out of water, and she told us to go to the house and fill the canteen. I suppose we were about 100 yards from the well. Wayne was in front of me, and we were barefoot. About halfway there Wayne screamed. Well, a rattlesnake had bit him on the ankle. My mom came running and screamed at my dad, and he just I left that team of mules right in the field. Even jumped about a four-strand barbed wire fence to get to us. They took Wayne to the house and did all the home remedies that they knew about in those days for rattlesnake bite. But it didn't do any good.

My dad had a little Model T Ford then. They bundled Wayne up, and we headed for town, about a two and a half-hour drive to get to a doctor. That was the first time I had ever gone to town. In those days they didn't have the anti-toxin, anti-venom for rattlesnake bites. They had several doctors with my brother, but he lived three days and then died. (2-3)

I truthfully didn't have any ambitions about show business at that time, mainly because of my eyes. The only cross-eyed guy I ever knew that made any money was Ben Turpin, a movie actor who played a cross-eyed comedian. I thought, "Well, maybe that's what I'll do. I'll just be a Ben Turpin." I clowned around a lot as a kid. (8)

I worked one summer in Phoenix mixing mud for two plasterers. One of them was my dad, and the other was a man named Del Webb. We all knew Del. He did pretty well after he quit plastering. (10)

Then I got a job with a group out of Philadelphia called the Sleepy Hollow Gang. They were on a big 50,000-watt radio station, WCAU, and had a morning show. . . .

Anyway, I think I realized I could make it at Sleepy Hollow Ranch at those Sunday things in the summertime. I used to put a sack over my shoulders and sell candy during intermissions. You did everything. Greased the ferris wheel and put it up, whatever needed to be done. You were singing for the ranch, but you had to do all the other jobs to boot. When it came time to entertain, you'd wash your hands, go on the stage, and sing and pick with the group during the show. (11)

I went in on a Monday morning to the Credit Union at the radio station and borrowed $75 to pay for it. I had to borrow it, because I really didn't have $75.

They just gave me a local anesthetic, popped my eye out of my head and worked on the thing and put an adjustable stitch it, which they pasted up to my forehead. I put on some dark glasses, and didn't even miss a radio show or a Barn Dance. I'd go back into that clinic every day after my morning show, and he would put a bracket on my head and readjust those stitches. If it was a little off, he'd move it and tie it. I think that thing was on for about two weeks.

And then a whole new world opened up. Just a whole new world. My eyes were straight.

All of a sudden my whole life changed. I started dating a beautiful girl; Foley went on to Nashville; Curt Massey went to Hollywood; and this whole town was wide open. I fell into it like a pillow in the ocean. It was 1946, my weekly income I lent from about $50 to $1,500 a week overnight, and to make it complete, Bonnie and I got married. (16)

The first television show I did was in Chicago. Down in the State Lake Building, across from the Chicago Theater. At that time it was a closed circuit thing. There were only 80 TV sets in the whole city of Chicago. And the musician's union had not yet made a deal with television. I had to have a non-union guitar player stand in the wings and play for me. I couldn't even let him be seen. (22)

The first time I met Roy Rogers, I didn't even know I was meeting Roy Rogers, because his name then was Leonard Slye. It was at the Mystic Theater in Willcox back in the early thirties, 1933 to be exact. He was in there working for my cousin Curtis McPeters, "Cactus Mack," and they were the "O-Bar-O Cowboys." There was Len, Tim, Slumber and Cyclone, just singing those great cowboy songs right there on Railroad Avenue. Little did I know then, I was seeing two fellers who would later be a driving force in bringing western music to its peak: Tim Spencer and Roy Rogers, who created "The Sons of the Pioneers." (23)

But in that era there were several of us, like Elton Britt, Eddy Arnold, even Red Foley. Everybody yodeled. We'd sing a little song and we'd put a little yodel in the middle of it or on the end of it, like whistling. But it died out when the record business got big. You would get a standing ovation at a show or a county fair yodeling, but you cut a record of it and you couldn't give it away. It was funny. Real funny. (25)

I had very serious doubts as to whether I could make it as an actor. But I got there and found out I didn't have to be an actor anyway. Anybody could have done it.

So, they flew me out and gave me the limousine treatment, and the big suite at the Roosevelt Hotel, and drivers, and you know the bit. They picked me up at the hotel, took me out and put me in makeup. And I'd just never been around anything like that.

I felt in awe of the whole world there. Just the whole world. Right off the bat, I saw John Wayne. He was under contract at Republic, and I saw him my very first day. He knew what I was out there for. He just slapped me on the back and damn near knocked me down, and said, "Good luck, Kid. Welcome aboard." I'm damn near crying right now thinking about it. I felt just like a little kid in a dream. You know, I couldn't believe it was happening to me. (26)

When I arrived, the studio wouldn't let me do a thing. Not even a television guest shot. The studio people had promised the theater owners that I would not ever be seen on television, that I belonged to them. Mr. Yates thought television was just a passing fancy and would soon fade away. And if Gene and Roy wanted to do TV, let 'em do it. But Rex Allen would never be seen on the box. "Thanks a lot, Mr. Yates." (27)

I started with KoKo in my second picture, and had him for about nineteen years.

I traveled a million miles with him all over the country. It got to where neither one of us wanted to go very bad, but we did. We went to Canada, Mexico, New York, and everywhere.

And I swear, one time I was loading him up at the barn on the ranch at Malibu and, as I loaded him in the trailer, he turned his head around and looked me right in the eye as if to say, "Where in the hell are you taking me now?"

But you know he never made a mistake. Any mistake that was made was my fault. He was a good horse, and I was proud of him, and I still think he's the prettiest horse I ever saw.

Kids would come up and say, "Hi, Rex. Where's KoKo?"

I'd even get mail at the studio that said, "Sure like your movies, and you're a good singer. Please send me a picture of KoKo." (33-4)

Carl "Alfalfa" Switzer was my third sidekick. A little freckle-faced guy out of Our Gang comedies. Shortly after our one film together, a guy shot and killed Alfie over a $65 debt. (34)

They always hired a different leading lady for each of my pictures. There were a couple of girls, like Mary Ellen Kay, who made three or four, but they didn't want to establish a team anymore, like a Roy and Dale. Consequently, the girls were hired for one picture only. For one of the pictures, they hired a gal named Jeff Donnell. She was a damn fine actress and here I am a green country boy starting my third film, "Redwood Forest Trail."

Anyway, it's the first day on the film, and we had a shot standing somewhere together. The shot was in the middle of the script. You know, you don't start a film at the front and go; you start anywhere they want you to. We started shooting this thing up at Big Bear Lake. I didn't even know the girl, just met her.

Anyway, it's the first day on the film, and we had a shot standing somewhere together. The shot was in the middle of the script. You know, you don't start a film at the front and go; you start anywhere they want you to. We started shooting this thing up at Big Bear Lake. I didn't even know the girl, just met her.

"This is Miss Donnell," they said. "She's your leading lady in this movie." And I'm trying to remember lines and all this stuff. I don't know the girl, really, other than to say "Hi, Jeff, nice to see you, and I'm glad to have you on the picture, and I hear you're great. It'll be fun working with you."

So we're standing there for the first shot, the camera is right head on to us, and I'm trying to think my lines so I don't mess up.

The director said, "Let's rehearse it. Alright. ACTION." I forget what the line was, but I said something to her and she said something to me. And while she's talking, she reached over and pinched me on the butt. Out of camera. Couldn't see it or nothing. Just pinched me on the butt, She said, ''I'll bet you cheat on your wife, don't you?"

Whooooooo—I thought, now I know I'm in Hollywood. Well, she didn't mean a damn thing by that. She just wanted to see if she could embarrass me, and she sure did. I was just shocked.

Jeff Donnell was the kind of gal with a sense of humor that made a long work day seem short. (35-6)

Let's say we were on location. You'd have a makeup call about 5:30 a,m. at the studio. You go into makeup, then put on your wardrobe, and a car would drive you out to location. They wouldn't let us drive because a union man had to do it. You dealt with 32 unions before you could roll a foot of film. (37)

I was talking a while ago about sanitary engineers. They were the guys that raked up the horse manure on the street and put it in barrels. You never saw any in our westerns. It was immoral to show a thing like that. I always wanted to make a western that had some "road apples" on the street like it really was.

Speaking of those guys, there is a story they tell: They struck once, wanting more money. Somebody in the industry came up with the idea. "They really don't get much recognition. Why don't we call them 'Sanitary Engineers' and not give 'em a raise." That's what they did. Just gave 'em a title. (47, 50)

Walt was a fine man. Nobody called him Mr. Disney. He was Walt to everybody at the studio.

I did a thing for him for the World's Fair in New York called "The Carousel of Progress" for General Electric. I don't know why he chose me to narrate that; it was not a nature show; it was a modern-type thing. I did the music on it, the songs to open it. They had a figure built out of a plastic material full of electronics. And this figure was capable of gestures, cross his legs, move his arms, take a newspaper and move it, and talk to the dog.

Well, it played at the World's Fair for a year in New York, and when it finished, he moved it back to Disneyland and it ran 12 years there, eight times a day. I pity the poor people who worked in that theater, they had to listen to me eight times a day for twelve years. I'm sure the ones that quit, quit for that reason. They had to listen to this old cowboy again and again. Then it was moved to Disney World in Florida. (57)

About the second or third Rex Allen Days celebration in Willcox, the big parade was going on, and the marching bands, and all that stuff—and here I came around the corner. I was dressed in this wild rhinestone outfit, and the guns, and KoKo with his silver saddle, and he's prancing down the street. I'm waving my hat, and my Dad's standing over on the corner with three old widow gals. Big old tall, six foot four, handsome guy, and he's just standing there with them watching. One of them said to him, "Horace, you must be awful proud of that boy."

And he said, "Well, I guess I am,"

She said, "I sure wish I had a boy like that."

My Dad said, "Well, if you old girls hadn't a been so damn particular a few years ago, everyone of you coulda' had one." (92-4)

Bonnie and I really loved the ranch. It was just a perfect place to raise children, and they learned a lot. They all became good horsemen. All my sons can do a little welding, a little carpenter work. They can fix a car. And thank God, none of them ever got into alcohol and dope. I think you just kind of luck out today on that. (100)

Yakima Canutt never did work on any of my films. He used to come around and visit the set once in awhile because all the stunt men admired him so much. Joe Yrigoyen did most of the doubling for me; same guy that doubled for Roy Rogers and Gene Autry. The whole Yrigoyen family, his brother Bill and allI of them, were stuntmen. But Yakima Canutt taught 'em all and could tell them how the cow eat the cabbage. (107)

Tex Ritter: A sweetheart. A lot of people don't know it, but Tex had a law degree. He lived about two blocks from me when I first moved out there. We had boys about the same age. They grew up in the neighborhood and ran around together. Ritter never had an enemy in his life. When I first went out there, I was told, "You're going to meet a lot of people out here that are not truthful, and you're going to meet some that are kind of phony, and you're going to meet some great guys, but if anybody ever says anything bad about Tex Williams or Tex Ritter, look out for that guy, because there's something wrong with him." (113)

|