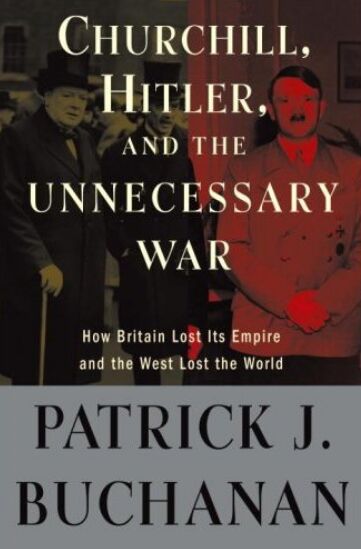

Churchill, Hitler, and the Unnecessary War

Patrick J. Buchanan - (2008)

There has arisen among America's elite a Churchill cult. Its acolytes hold that Churchill was not only a peerless war leader but a statesman of unparalleled vision whose life and legend should be the model for every statesman. To this cult, defiance anywhere of U.S. hegemony, resistance anywhere to U.S. power becomes another 1938. Every adversary is "a new Hitler," every proposal to avert war "another Munich." Slobodan Milosevic, a party apparatchik who had presided over the disintegration of Yugoslavia—losing Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, and Bosnia—becomes "the Hitler of the Balkans" for holding Serbia's cradle province of Kosovo. Saddam Hussein, whose army was routed in one hundred hours in 1991 and who had not shot down a U.S. plane in forty thousand sorties, becomes "an Arab Hitler" about to roll up the Persian Gulf and threaten mankind with weapons of mass destruction. (xix-xx)

"[Lloyd George] was sickened by the huge crowds jubilantly thronging Whitehall and Parliament Square and his face was white as he sat slumped in his seat in the Commons," listening to Grey make the case for war. Cheered on his way to Parliament, Lloyd George muttered: "This is not my crowd .... I never want to be cheered by a war crowd." (43)

Churchill was exhilarated. Six months later, after the first Battle of Ypres, with tens of thousands of British soldiers in their graves, he would say to Violet Asquith, "I think a curse should rest on me—because I am so happy; I know this war is smashing and shattering the lives of thousands every moment and yet—I cannot help it—I enjoy every second. " (43-4)

White had several conversations with Balfour, one of which was overheard by White's daughter, who took notes:

Balfour (somewhat lightly): "We are probably fools not to find a reason for declaring war on Germany before she builds too many ships and takes away our trade."

White: "You are a very high-minded man in private life. How can you possibly contemplate anything so politically immoral as provoking a war against a harmless nation which has as good a right to a navy as you have? If you wish to compete with German trade, work harder."

Balfour: "That would mean lowering our standard of living. Perhaps it would be simpler for us to have a war."

White: "I am shocked that you of all men should enunciate such principles."

Balfour (again lightly): "Is it a question of right or wrong? Maybe it is just a question of keeping our supremacy." (49)

An anecdote related by British naval historian Russell Grenfell in his Unconditional Hatred has about it the ring of historical truth:

British embroilment in the war of 1914-18 may be said to date from January 1906, when Britain was in the throes of a General Election. Mr. Haldane, the Secretary of State for War, had gone to the constituency of Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, to make an electioneering speech in his support. The two politicians went for a country drive together, during which Grey asked Haldane if he would initiate discussions between the British and French General staffs in preparation for the possibility of joint action in the Tevent of a Continental war. Mr. Haldane agreed to do so. The million men who were later to be killed as a result of this rural conversation could not have been condemned to death in more haphazard a fashion. (64)

In January of 1915, half a year into the war, with tens of thousands of British soldiers already in their graves, including his own friends, Churchill, according to Margot Asquith's diary account, waxed ecstatic about the war and his historic role in it:

My God! This is living History. Everything we are doing and saying is thrilling—it will be read by a thousand generations, think of that! Why I would not be out of this glorious delicious war for anything the world could give me (eyes glowing but with a slight anxiety lest the word "delicious"should jar on me). (66)

Those three all-powerful, all-ignorant men ... sitting there carving continents with only a child to lead them. — Arthur Balfour (69)

"Democracy is more vindictive than Cabinets," Churchill had told the Parliament in 1901. "The wars of peoples will be more terrible than those of kings." The twentieth century would make a prophet of the twenty-six-year-old MP. And the peace the peoples demanded and got in 1919 would prove more savage, for, wrote one historian, "it was easier for despotic monarchs to forget their hatreds than for democratic statesmen or peoples." [.PDF] (72-3)

Lloyd George enlisted South Africa's Jan Smuts, a lawyer one historian calls "the great operator of fraudulent idealism," to persuade Nilson that forcing Germany to fund the pensions of Allied soldiers would not violate his pledge to limit reparations to civilian damage done in the war. An outraged U.S. delegation implored Wilson to veto the reparations bill, arguing that it did not follow logically from any of his Fourteen Points.

"Logic, logic, I don't give a damn about logic," Wilson snarled. "I am going to include pensions." Henry White, one of five members of the official U.S. delegation, reflected the dejection and disillusionment idealistic Americans felt: "We had such high hopes of this adventure; we believed God called us and now we are doing hell's dirtiest work." (75)

WHY DID THE GERMANS SIGN?

Germany faced invasion and death by starvation if she refused. With her merchant ships and even Baltic fishing boats sequestered, and the blockade still in force, Germany could not feed her people. When Berlin asked permission to buy 2.5 million tons of food, the request was denied. From November 11 through the peace conference, the blockade was maintained. Before going to war, America had denounced as a violation of international law and human decency the British blockade that had kept the vital necessities of life out of neutral ports if there were any chance the goods could be transshipped to Germany. But when America declared war, a U.S. admiral told Lord Balfour, "You will find that it will take us only two months to become as great criminals as you are."

U.S. warships now supported the blockade. "Once lead this people into war," Wilson had said in 1917, "and they'll forget there ever was such a thing as tolerance." America had forgotten. The blockade was responsible for the deaths of thousands of men, women, and children after the Germans laid down their weapons and surrendered their warships. Its architect and chief advocate had been the First Lord of the Admiralty. His aim, said Churchill, was to "starve the whole population—men, women, and children, old and young, wounded and sound—into submission." On March 3,1919, four months after Germany accepted an armistice and laid down her arms, Churchill rose exultant in the Commons to declare, "We are enforcing the blockade with rigour, and Germany is very near starvation."

Five days later, the Daily News wrote, "The birthrate in the great towns [of Germany] has changed places with the death rate. It is tolerably certain that more people have died among the civil population from the direct effects of the war than have died on the battlefield." (77-9)

In 1938, a British diplomat in Germany was asked repeatedly, "Why did England go on starving our women and children long after the Armistice?" "Freedom and Bread" would become a powerful slogan in the ascent to power of the new National Socialist Workers Party. (80)

By forcing German democrats to sign the Treaty of Versailles, which disarmed, divided, and disassembled the nation Bismarck had built, the Allies had discredited German democracy at its birth. (83)

France was forced to settle for a fifteen-year occupation. But the price Clemenceau exacted for giving up any claim to the Rhineland was high: an Anglo-American-French alliance. Under a Treaty of Guarantee, America and Britain were to be obligated to come to France's aid should Germany attack her again.

Incredibly, Wilson agreed, though he knew such an alliance violated a cardinal principle of U.S. foreign policy since Washington: no permanent alliances. (86)

So it was that the men of Paris redrew the maps of Europe, and planted the seeds of a second European war. (95)

The treaty writers of Versailles wrote the last act of the Great War and the first act of the resurrection of Germany and the war of retribution. Even in this hour men saw what was coming: Lloyd George in his Fontainebleau memorandum; Keynes as he scribbled notes for his Economic Consequences of the Peace; Foch ("This is not peace, it is an armistice for twenty years"); and Smuts ("This Treaty breathes a poisonous spirit of revenge, which may yet scorch the fair face—not of a corner of France but of Europe)." (98)

Versailles had created not only an unjust but an unsustainable peace. Wedged between a brooding Bolshevik Russia and a humiliated Germany were six new nations: Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. The last two held five million Germans captive. Against each of the six, Russia or Germany held a grievance. Yet none could defend its independence against a resurrected Germany or a revived Russia. Should Russia and Germany unite, no force on Earth could save the six. (98)

In dealing with the defeated the statesmen of Versailles not only ignored the "imperative principle," they violated it again and again and again. In a letter home, May 31, 1919, Charles Seymour, head of the Austro-Hungarian division of the American delegation and future president of Yale, described a memorable scene:

We went into the next room where the floor was clear and Wilson spread out a big map (made in our office) on the floor and got down on his hands and knees to show us what had been done; most of us were also on our hands and knees. I was in the front row and felt someone pushing me, and looked around angrily to find that it was Orlando [Italian premier and leader of the Italian delegation to the conference] on his hands and knees crawling like a bear toward the map. I gave way and he was soon in the front row. I wish that I could have had a picture of the most important men in the world on all fours over this map.

Thus were sown the seeds of the greatest war in the history of mankind.

Point 18 declared that "all well-defined national aspirations shall be accorded the utmost satisfaction ... without introducing new ... elements of discord and antagonism that would be likely in time to break the peace of Europe and consequently of the world."

Point 18 is a parody of what was done at Paris.

There was scarcely a promise Wilson made to the Germans at the time of the armistice that was not broken, or a principle of his that he did not violate. The Senate never did a better day's work than when it rejected the Treaty of Versailles and refused to enter a League of Nations where American soldiers would be required to give their lives enforcing the terms of so dishonorable and disastrous a peace. (109-10)

At a London dinner party soon after Adolf Hitler had taken power in Berlin, one of the guests asked aloud, "By the way, where was Hitler born?"

"At Versailles" was the instant reply of Lady Astor. (110)

At Versailles, [Billy] Hughes had sassed President Wilson to his face. When Wilson asked if Australia was willing to risk the failure of the peace conference and a dashing of the hopes of mankind over a few islands in the South Pacific, Hughes, adjusting his hearing aid, cheerfully replied, "That's about the size of it, Mr. Wilson." (114-15)

All agreed that if the Americans would offer a U.S.-British alliance to replace the Anglo-Japanese treaty, it should be taken up. But no such offer was on the table. Given the U.S. aversion to alliances—the nation had not entered a formal alliance since the Revolutionary War—America was not going to offer Britain war guarantees for her Asian colonies. U.S. Marines were not going to fight for Hong Kong. (116)

[Charles Evans] Hughes was calling for a ten-year holiday in shipbuilding and the scuttling of British, U.S., and Japanese capital ships until the three navies reached a 5-5-3 ratio. Britain and the United States would be restricted to 500,000 tons, Japan to 300,000. No warship would be allowed to displace more than 35,000 tons. Hughes's plan spelled an end to the British super-ships. (118)

Japan took her inferior number as a national insult. This looks to us like "Rolls Royce-Rolls Royce-Ford," said one Japanese diplomat. Yet the ratios would enable Japan to construct a fleet 60 percent of Britain's, though Japan had only the western Pacific to patrol while Britain had a global empire. (120)

There was a second reason why Britain surrendered naval supremacy. The national debt had exploded fourteenfold during the war. Half the national tax revenue was going for interest. Lloyd George feared that if Britain took up the U.S. challenge to her naval supremacy by building warships, Americans would demand immediate payment of her war debts. The Yankees now held the mortgage on the empire. (122)

The energetic Stimson, however, who had come to believe that nonintervention in foreign quarrels was an obsolete policy, responded with the "Stimson Doctrine": The United States would refuse to recognize any political change effected by means "contrary to the covenants and obligations of the Pact of Paris." Initially rebuffed by the British Foreign Office, which did not consider Britain obligated to defend the territorial integrity of China—an ideal that had never been a reality—Stimson soon brought the British around to his view. It was also adopted by the League of Nations. Thus did Stimson put America and Britain on the path to war with Japan. (127)

Mussolini had been in power for a decade before Hitler ever became Chancellor. During that decade, Il Duce's attitude toward the Nazi leader may be summed up in a single word: contempt. But Hitler's admiration for Il Duce bordered on adulation. As leader of the National Socialist Party in 1927, Hitler had, through the Berlin head of the Italian Chamber of Commerce, requested a signed photograph of Il Duce. Across the memorandum Mussolini scrawled in bold letters, "Request refused." (132)

As the British Empire controlled almost every other piece of real estate in East Africa, Italy's annexation of part or all of Ethiopia posed no threat to Great Britain. And with British flags flying over Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaya, Burma, India, Ceylon, Pakistan, southern Iran, Iraq, Palestine, Egypt, the Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, Tanganyika, Rhodesia, South Africa, Southwest Africa, Togo, the Gold Coast, and Nigeria—not all acquired by peaceful purchase—for Britain to oppose Italy's annexation of Ethiopia might seem hypocritical. To aspiring imperial powers like Italy and Japan, it did. Yosuke Matsuoka, who had led the Japanese delegation at Geneva, had commented about the centuries-old practice of imperialism: "The Western powers taught the Japanese the game of poker but after acquiring most of the chips they pronounced the game immoral and took up contract bridge." (149-50)

America ignored Hitler's move because she had turned her back on European power politics. Americans had concluded they had been lied to and swindled when they enlisted in the Allied cause in 1917. They had sent their sons across the ocean to "make the world safe for democracy," only to see the British empire add a million square miles. They had been told it was a "war to end wars." But out of it had come Lenin, Stalin, Mussolini, and Hitler, far more dangerous despots than Franz Josef or the Kaiser. They had lent billions to the Allied cause, only to watch the Allies walk away from their war debts. They had given America's word to the world that the peace imposed on Germany would be a just peace based on the Fourteen Points and Wilson's principle of self-determination, then watched the Allies dishonor America's word by tearing Germany apart, forcing millions of Germans under foreign rule, and bankrupting Germany with reparations. (167-8)

When French Premier Edouard Daladier flew home from Munich, he was stunned to see a huge throng gathered at Le Bourget. He circled the field twice, fearful the crowd was there to stone him for having capitulated to Hitler and betrayed France's Czech allies by forcing them to surrender the Sudetenland. Daladier was astonished to find the crowd rejoicing and waving him home as a hero of peace. (207)

The British press outdid the Americans. The morning after the prime minister's return, the London Times's story began: "No conqueror in history ever came home from a battlefield with nobler laurels." Margot Asquith, widow of the prime minister who had led Britain into the Great War, called Chamberlain the greatest Englishman who had ever lived. Old ladies "suggested that Chamberlain's umbrella be broken up and pieces sold as sacred relics." From exile in Holland, the Kaiser wrote Queen Mary of his happiness that a catastrophe had been averted and that Chamberlain had been inspired by heaven and guided by God Himself. The clerics rejoiced. (207-8)

Not all joined the celebration. The Daily Telegraph was caustic and cutting: "It was Mr. Disraeli who said that England's two greatest assets in the world were her fleet and her good name. Today we must console ourselves that we still have our fleet." (208-9)

Chamberlain, however, must have sensed he had not really brought home "peace for our time." In the triumphal ride to Buckingham Palace, he had confided to Halifax, "All this will be over in three months." (210)

At Paris, 3.25 million German inhabitants of Bohemia and Moravia had been transferred to the new Czechoslovakia of Tomas Masaryk and Eduard Benes in a flagrant disregard of Wilson's self-proclaimed ideal of self-determination. Asked why he had consigned three million Germans to Czech rule, Wilson blurted, "Why, Masaryk never told me that!" (213)

Chamberlain thought it a "truly wonderful visit." In describing his British guests to his son-in-law, Foreign Minister Count Ciano, Mussolini had taken away another impression: "These men are not made of the same stuff as the Francis Drakes and the other magnificent adventurers who created the empire. These, after all, are the tired sons of a long line of rich men, and they will lose their empire." (237)

In words drafted by Halifax, Neville Chamberlain had turned British policy upside down. The British government was now committed to fight for Poland. With this declaration, writes Ernest May,

"a government that a half-year earlier had resisted going to war for a faraway country with democratic institutions, well-armed military forces, and strong fortifications, now promised with no apparent reservations to go to war for a dictatorship with less-than-modern armed forces and wide open frontiers." (255)

Churchill's 1948 depiction of Britain's situation on the day of the war guarantee to Poland is absurd. On March 31,1939, Britain was not facing a "precarious chance of survival." Hitler had neither the power nor desire to force Britons to "live as slaves." He wanted no war with Britain and showed repeatedly he would pay a price to avoid such a war. It was the Poles who were facing imminent war with only a precarious chance of survival." It was the Poles who might end up as "slaves" if they did not negotiate Danzig. That they ended up as slaves of Stalin's empire for half a century, after half a decade of brutal Nazi occupation, as a consequence of their having put their faith in a guarantee Chamberlain and Churchill had to know was worthless when it was given. (259)

Thus did the British government, in panic over a false report about a German invasion of Poland that was neither planned nor prepared, give a war guarantee to a dictatorship it did not trust, in a part of Europe where it had no vital interests, committing itself to a war it could not win. Historian [Paul] Johnson's depiction of Chamberlain's decision as reckless and irrational is an understatement. (262)

A. J. P. Taylor describes how Beck received word that Great Britain would defend Poland to the death:

The [British] ambassador read out Chamberlain's assurance. Beck accepted it "between two flicks of the ash off his cigarette." Two flicks; and British grenadiers would fight for Danzig. Two flicks; and the illusory great Poland, created in 1919, signed her death warrant. The assurance was unconditional: the Poles alone were to judge whether it should be called upon. The British could no longer press for concessions over Danzig.

Two flicks of the ash off the colonel's cigarette and the fate of the British Empire and fifty million people was sealed. (264)

Lloyd George believed that Chamberlain's "hare-brained pledge" had been an impulsive reaction to his humiliation:

Hitler having fooled him, he felt he must do something to recover his lost prestige, so he rushed into the first rash and silly enterprise that entered his uninformed mind. He guaranteed Poland, Roumania and Greece against the huge army of Germany.... (266)

Rather than see Poland return Danzig to the Reich, Halifax preferred that Poland fight Germany to the death in a war Halifax knew Poland could not win, because the British could not help. To Halifax, Poland's suicide was preferable to having Hitler chalk up "yet another bloodless coup." The Holy Fox appears to have had no reservations about pushing Poland to its death in front of Hitler's war machine—to exhibit "his willingness to fight for ... the 'great moralities.' "

Such is the morality of Great Powers. (268)

Goaded by Halifax, stampeded by Tory backbenchers and a jingo press into issuing his war guarantee, Chamberlain would get the war he never wanted, and Churchill would get the war he had sought to bring about. To them both belongs the responsibility for what happened to Britain. But what Chamberlain did to the Poles, issuing a war guarantee he knew was worthless, was far worse than what he had done to the Czechs. At least he had told the Czechs the truth: Britain would not fight for the Sudetenland. But Poles put their trust in their war guarantee and security pact with Great Britain. They were repaid for that trust with abandonment and half a century of Nazi and Soviet barbarism.

"In 1938," writes A. J. P. Taylor, "Czechoslovakia was betrayed. In 1939, Poland was saved. Less than one hundred thousand Czechs died during the war. Six and a half million Poles were killed. Which was better—to be a betrayed Czech or a saved Pole?" (281)

On May 5, Colonel Beck rose in the Polish Diet and rejected both the German version of negotiations and Hitler's offer to start anew. (283)

Beck would refuse even to discuss Danzig with the Germans, and the British would refuse to press Beck to negotiate. Hitler thus concluded that Britain was behind Poland's intransigence, and that Britain was committed to war to prevent Danzig's return. The conclusion is understandable. The conclusion was wrong. For Chamberlain still believed Germany's case for Danzig was her strongest territorial claim and favored the return of the city, if only Hitler would go about it peacefully—which was exactly what Hitler, at that point, was still trying to do.

In the final fateful week of August 1939, as Hitler desperately cast about for a way to keep Britain out of his war with Poland, British leaders were desperately casting about for a way to convince the Poles to effect a peaceful return of Danzig to Germany.

It was the war guarantee—that guaranteed the war. (284)

Consider the hellish situation Stalin faced in March 1939. A pariah state with a reputation for mass murder and an archipelago of slave-labor camps, the USSR was isolated from the Western democracies, hated and feared by its neighbors, and threatened by Nazi Germany and by Japan in the Far East. Stalin knew a goal that motivated the man who wrote Mein Kampf and now ruled Germany was the extermination of Bolshevism.

He had watched Hitler annex Austria, carve the Sudetenland out of Czechoslovakia, turn Bohemia and Moravia into protectorates and Slovakia into an ally, retake Memel, and begin to move on Poland without a shot being fired. Stalin knew: After Poland, his turn would come. That would mean a Nazi-Bolshevik war in which he must face Germanic power alone.

On March 31, 1939, came deliverance. Britain and France declared they would fight for Poland, the buffer state between Russia and Germany. British Tories had become the guarantors of Bolshevism. Moscow had been given free what Stalin would have paid a czar's ransom for. (300)

Had Britain never given the war guarantee, the Soviet Union would almost surely have borne the brunt of the blow that fell on France. The Red Army, ravaged by Stalin's purge of senior officers, might have collapsed. Bolshevism might have been crushed. Communism might have perished in 1940, instead of living on for fifty years and murdering tens of millions more in Russia, China, Korea, Vietnam, and Cuba. A Hitler-Stalin war might have been the only war in Europe in the 1940s. Tens of millions might never have died terrible deaths in the greatest war in all history. (301)

After Dunkirk, with the fall of France imminent, Mussolini saw history passing him by: "I can't just sit back and watch the fight. When the war is over and victory comes I shall be left empty handed!"

"Mussolini had long been champing at the bit to grab a piece of French territory as well as a crumb of the glory," writes Alistair Horne. "He told Marshal Badoglio: 'I need only a few thousand dead to ensure that I have the right to sit at the peace table in the capacity of a belligerent.'" (303)

That fall, Mussolini's armies invaded Egypt and Greece, where they quickly floundered. To rescue his ally, Hitler sent armies into the Balkans and North Africa. Thus, by June 1941, Hitler occupied Europe west to the Pyrenees and south to Crete. These conquests had come about not because of some Hitlerian master plan, but be cause of a war with Britain that Hitler had never wanted, and an invasion of Greece by Mussolini that Hitler had opposed. (304)

Most of the fighting and dying in the bloodiest of all wars, to bring down Hitler's Reich, was done on the Eastern Front. As Davies writes, "The Third Reich was largely defeated not by the forces of liberal democracy, but by the Red Army of another mass murdering tyranny. The liberators of Auschwitz were servants of a regime that ran an even larger network of concentration camps of its own."

Measured by the size of the armies, the scope of the battles, and the length of the casualty lists, World War II was less a war between Fascism and freedom than a war between Nazism and Bolshevism. Hitler lost, Stalin won. (309)

As the Battle of Britain was under way, on August 14, 1940, Hitler called his newly created field marshals into the Reich Chancellery to impress upon them that victory over Britain must not lead to a collapse of the British Empire:

"Germany is not striving to smash Britain because the beneficiaries will not be Germany, but Japan in the east, Russia in India, Italy in the Mediterranean, and America in world trade. This is why peace is possible with Britain—but not so long as Churchill is prime minister. Thus we must see what the Luftwaffe can do, and wait a possible general election."

Hitler is here telling his military high command that the air war over England, the Battle of Britain, was not designed to prepare for invasion but to bring down Churchill. From his actions in the west, from 1933 through 1939, there is compelling evidence Hitler wanted to see the British Empire endure. And if he did not wish to bring down the British Empire, how can it be argued that Hitler was out to conquer the world? (328)

On the eve of the war of 1914-1918, Churchill described the Kaiser, who was then casting about desperately for some way to avoid a war, as a "continental tyrant" whose goal was "the dominion of the world."

When Haldane and Churchill claimed the Kaiser was a "continental tyrant" out for "dominion of the world," Wilhelm II was in late middle age, had been in power twenty-five years, and had yet to fight his first war.

In his 1937 Great Contemporaries, Churchill exonerates the Kaiser of the charge of which he had accused him before the war of 1914: "[H]istory should incline to the more charitable view and acquit William II of having planned and plotted the World War."

In the same book, Churchill wrote of Hitler, "Whatever else may be thought about these exploits, they are among the most remarkable in the whole history of the world." Churchill was referring not only to Hitler's political achievements, but his economic achievements. (336)

I do not care so much for the principles I advocate as for the impression which my words produce and the reputation they give me. — Winston Churchill, 1898

Winston has no principles. — John Morley, 1908 (Cabinet Colleague)

Churchill will write his name in history; take care that he does not write it in blood. — A. G. Gardiner, 1913 Pillars of Society

As the twentieth century ended, a debate ensued over who had been its greatest man. The Weekly Standard nominee was Churchill. Not only was he Man of the Century, said scholar Harry Jaffa, he was the Man of Many Centuries. To Kissinger he was "the quintessential hero." A BBC poll of a million people in 2002 found that Britons considered Churchill the "greatest Briton of all time." (351)

Churchill had to know in 1939, when he was pounding the war drums and calling for partnership with Stalin, that any victory in alliance with Stalin would bring Communism into the heart of Europe and replace Nazi tyranny with Bolshevik tyranny. Was it worth bankrupting and bleeding his country and bringing down the empire for this? Was it worth declaring war to keep 350,000 Danzigers separate from a Germany they wished to rejoin, if the cost was to consign one hundred million people to the mercy of Stalin's butchers? (375)

Churchill knew of the mass murders on Lenin's orders, the massacre of the Czar's family, Stalin's slave-labor camps, the forced starvation in Ukraine, the Great Purge of the old comrades and Russian officer corps, the show trials, the pact with Hitler, the rape of Finland and the Baltic republics, Katyn. As historian John Lewis Gaddis writes, "[T]he number of deaths resulting from Stalin's policies before World War II ... was between 17 and 22 million," a thousand times the number of deaths attributed to Hitler as of 1939, the year Churchill was clamoring for war on Hitler and an alliance with Stalin. (375)

At Yalta, Churchill raised a glass to Stalin:

It is no exaggeration or compliment of a florid kind when I say that we regard Marshal Stalin's life as most precious to the hopes and hearts of all of us. . . . I walk through this world with greater courage and hope when I find myself in a relation of friendship and intimacy with this great man, whose fame has gone out not only over all Russia, but the world.

Allowances may be made for toasts between heads of state on foreign soil, but they do not extend to remarks made when Churchill returned from the summit that will live in infamy alongside Munich.

"Poor Neville Chamberlain believed he could trust Hitler. He was wrong. But I don't think I'm wrong about Stalin," Churchill said on his return from Yalta. He declared to the House, "I know of no Government which stands to its obligations, even in its own despite, more solidly than the Russian Soviet Government." "This must surely rank as one of the most serious political misjudgments in history," wrote Royal Navy captain and historian Russell Grenfell. (376-7)

On March 5, 1946, Churchill would be in Fulton, Missouri, declaring, "From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent." Churchill was describing the line he and the Old Bear had drawn up together at Teheran, Moscow, and Yalta. (377)

More than "ally himself to Stalin," Churchill colluded with Stalin in such historic crimes as the forcible return of millions of resisting paws and Russians, whether "Soviet citizens" or not, from Allied occupied territory to the NKVD. Stalin was especially interested in the Cossacks who had fought Soviet rule in the civil war of1919-1920 and fled with their families to the West. Though they had never been "Soviet citizens," the Cossacks were sent back. As Solzhenitsyn writes in The Gulag Archipelago,

"In Austria that May [1945], Churchill ... turned over to the Soviet command the Cossack corps of 90,000 men. Along with them, he also handed over many wagonloads of old people, women, and children who did not want to return to their native Cossack rivers. This great hero, monuments to whom will in time cover all England, ordered that they, too, be surrendered to their deaths." (379)

At Yalta in February 1945, Churchill and FDR sought to limit the German lands ceded to Poland, but capitulated to Stalin's demand that the new provisional Polish-German border be set at the Oder and western Neisse rivers. This meant "11 million people—9million inhabitants of the eastern German provinces, and 2 million from Old Poland and the Warta District" would be driven out of their homes.

Two million Germans would die in this largest forced transfer of populations in history, a crime against humanity of historic dimensions in which twenty times as many Germans were driven from their homes between 1944 and 1948 as the 600,000 Palestinians of the war of 1948, and more Germans died than all the Armenians who perished in the Turkish massacres of World War 1. The territories of East Prussia, Pomerania, Eastern Brandenburg, Silesia, Danzig, Memel, and the Sudetenland were relentlessly and ruthlessly "cleansed" of Germans, whose families had inhabited them for centuries. While this crime against humanity was being perpetrated, the Allies at Nuremberg, including Stalin's USSR, were prosecuting the Germans for crimes against humanity. Alfred M. de Zayas, an American historian of the horror, says Churchill "knew what was going on."

"The responsibility for the decision to uproot and resettle millions of human beings, to evict them from their homes and spoliate them—and this as a quasi-peacetime measure—is ... a war crime for which individuals bear responsibility, even if many would still hesitate to put the correct label on the crime and its perpetrators."

To Anne O'Hare McCormick of the New York Times, Churchill and FDR acquiesced in "the most inhuman decision ever made by governments dedicated to the defense of human rights." (381-2)

As late as November 1945, Churchill, though out of power, was again praising Stalin so effusively—"this truly great man, the father of his nation"&3151;that Molotov ordered Churchill's speech published in Pravda. (383)

There is, however, no supporting evidence that Churchill ever made any sustained effort to end the starvation blockade he imposed as First Lord in August 1914.

WhiIe Germany introduced poison gas to the battlefield, Churchill became an enthusiast of its use against enemies of the empire. When the Iraqis resisted British rule in 1920, Churchill, as Secretary for War and Air, wrote Sir Henry Trenchard, a pioneer of air warfare: "I do not understand this squeamishness about the use of gas .... I am strongly in favor of using poisoned gas against uncivilised tribes [to] spread a lively terror." (391)

Churchill led the West into adopting the methods of barbarism of their totalitarian enemies. By late 1940, writes Johnson, "British bombers were being used on a great and increasing scale to kill and frighten the German civilian population in their homes." (392)

What Churchill had been describing to Stalin was a British policy to "de-house" the civilian population of Germany. Who was instigator and architect of the policy to carpet-bomb German cities? Frederick Lindemann, "the Prof," an intimate of Churchill's whom he had brought into his war Cabinet as science adviser. Lindemann had "an almost pathological hatred for Nazi Germany, and an almost medieval desire for revenge." (394)

Though British propaganda broadcasts charged that the Luftwaffe had begun the bombing of cities by brutally targeting London, Spaight believed that British cities might have been spared had Churchill not first resorted to city bombing: "There was no certainty, but there was a reasonable probability that our capital and our industrial centres would not have been attacked if we had continued to refrain from attacking those of Germany."

"To achieve the extirpation of Nazi tyranny there are no lengths of violence to which we will not go," Churchill told Parliament on September 21, 1943. By 1944, he had come back around to the idea of using chemical and biological warfare on civilians. In one secret project, he commissioned the preparation of five million anthrax cakes to be dropped onto the pastures of north Germany to poison the cattle and through them the people. As the Glasgow Sunday Herald reported in 2001,

"The aim of Operation Vegetarian was to wipe out the German beef and dairy herds and then see the bacterium spread to the human population. With people then having no access to antibiotics, this would have caused many thousands—perhaps even millions—of German men, women and children to suffer awful deaths.

The anthrax cakes were tested on Gruinard Island, off Wester Ross Island in Scotland, which was not cleared of contamination until 1990. (395-6)

In a memo to his air chiefs, Churchill acknowledged what Dresden had been about: "It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed." Sensing they were about to be scapegoated for actions Churchill himself ordered, the air chiefs returned the memo. In his1947 memoir, Bomber Offensive, Air Marshal Harris implies that Churchill gave the order to incinerate Dresden: "I will only say that the attack on Dresden was at the time considered a military necessity by much more important people than myself." (398)

Americans, too, played a role in adopting methods of barbarism from which earlier generations would have recoiled in horror and disgust. During World War I, we condemned the British starvation blockade before we went in, but supported it with our warships after we went in. If Churchill initiated terror bombing, America perfected it. Boasted Curtis LeMay of his famous raid on Tokyo, "We scorched and honed and baked to death more people in Tokyo that night of March 9-10 than went up in vapor in Hiroshima and Nagasaki." (398-9)

When the Mental Deficiency Act was advanced to sterilize the feeble-minded and "other degenerate types," Asquith's government agreed to consider the measure. Writes Edwin Black, author of War Against the Weak,

Home Secretary Winston Churchill, an enthusiastic supporter of eugenics, reassured one group of eugenicists that Britain's 120,000 feeble-minded persons "should, if possible, be segregated under proper conditions so that their curse died with them and was not transmitted to future generations." The plan called for the creation of vast colonies.Thousands of Britain's unfit would be moved into these colonies to live out their days.

"Hitler's ultimately genocidal programme of 'racial hygiene' began with the kind of compulsory sterilization of the 'feeble-minded and insane classes' that Churchill urged on the British government," writes Lind, (400-01)

To Churchill, blood and race were determinant in the history of nations and civilizations. Introducing the peoples of the Sudan in The River War, his memoir of the campaign in which he had served under Kitchener, Churchill wrote:

"The qualities of mongrels are rarely admirable, and the mixture of the Arab and negro types has produced a debased and cruel breed, more shocking because they are more intelligent than the primitive savages. The stronger race soon began to prey upon the simple aboriginals .... All, without exception, were hunters of men."

To Churchill, Negroes were "niggers" or "blackamoors," Arabs"worthless," Chinese "chinks" or "pigtails," Indians "baboos," and South African blacks "Hottentots."

Churchill's physician Lord Moran wrote in his diary that, while FDR was thinking of the importance of a China of four hundred million, Churchill "thinks only of the color of their skin; it is when he talks of India and China that you remember he is a Victorian." (402-3)

Writing to the Palestine Commission in 1936, Churchill made his convictions clear: "I do not admit that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black people of Australia ... by the fact that a stronger race, a higher grade race ... has come and taken their place." (403)

During the war, Churchill ranted against Indian demands for independence. "I hate Indians," he said. "They are a beastly people with a beastly religion." Beseeched by Amery and the Indian viceroy to release food stocks in the wartime famine, "Churchill responded with a telegram asking why Gandhi hadn't died yet."

One may find like comments in other leaders of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty in two wars and prime minister for five years of the bloodiest war in history, was in a position to act on his beliefs. And he did.

Those racial beliefs were behind the uncompromising stand Churchill took on "what was then called coloured immigration from the British Commonwealth" in his last days as prime minister in the mid-1950s. Churchill was a restrictionist. His thinking paralleled that of Lord Salisbury, who had declared: "It is not for me merely a question of whether criminal negroes should be allowed in or not ... it is a question whether great quantities of negroes, criminal or not, should he allowed to come."

"Churchill's feelings were strongly in [Salisbury's] direction," writes historian Peter Hennessey. To the governor of Jamaica, Sir Hugh Foot, Churchill said in 1954 that were immigration from the Caribbean not halted, "we would have a magpie society: that would never do."

Colored immigration weighed heavily on his mind. Churchill told one interviewer, "I think it is the most important subject facing this country, but I cannot get any of my ministers to take notice." Writes Hennessey, "Just as [Churchill] was distressed by the break-up of the British Empire, he was, for all his imperial romance, deeply disturbed about its black or brown members coming to the mother country."

Future prime minister Harold Macmillan, in his diary entry on the Cabinet meeting of January 20, 1955, wrote: "More discussion about the West Indian immigrants. A Bill is being drafted—but it's not an easy problem. P.M. [Churchill] thinks 'Keep England White' a good slogan!" (403-4)

Looking back, Alan Clark was appalled by Churchill's groveling to the Americans:

"Churchill's abasement of Britain before the United States has its origins in the same obsession [with Hitler]. The West Indian bases were handed over; the closed markets for British exports were to be dismantled; the entire portfolio of (largely private) holdings in America was liquidated. 'A very nice little list,' was Roosevelt's comment when the British ambassador offered it. 'You guys aren't broken yet.'"

Before Lend-Lease aid could begin, Britain was forced to sell all her commercial assets in the United States and turn over all her gold. FDR sent his own ship, the Quincy, to Simonstown near Cape Town to pick up the last $50 million in British gold reserves.

"We are not only to be skinned but flayed to the bone," Churchill wailed to his colleagues. He was not far off. Churchill drafted a letter to FDR saying that if America continued along this line, she would "wear the aspect of a sheriff collecting the last assets of a helpless debtor." It was, said the prime minister, "not fitting that any nation should put itself wholly in the hands of another." Desperately dependent as Britain was on America, Churchill reconsidered, and rewrote his note in more conciliatory tones.

And FDR knew exactly what he was doing. "We have been milking the British financial cow, which had plenty of milk at one time, but which has now about become dry," Roosevelt confided to one Cabinet member.

Writes A. J. P. Taylor of how Roosevelt humbled Churchill:

"Great Britain became a poor, though deserving cousin—not to Roosevelt's regret. So far as it is possible to read his devious mind, it appears that he expected the British to wear down both Germany and themselves. When all independent powers had ceased to exist, the United States would step in and run the world." (408-9)

In the twin catastrophes of Western civilization, World Wars I and II, Britain was the indispensable nation and Churchill an indispensable man.

It was Britain's secret commitment to fight for France, of which the Germans were left unaware, that led to the world war with a Kaiser, who never wanted to fight his mother's country. It was Britain's declaration of war on August 4, 1914, that led Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and India to declare war in solidarity with the Mother Country and drew Britain's ally Japan into the conflict. It was Britain's bribery of Italy with promises of Habsburg and Ottoman lands in the secret Treaty of London in 1915 that brought Italy in. Had Britain not gone in, America would have stayed out."

It was Britain that converted a Franco-German-Russian war into a world war of four years that brought down the German, Russian, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian empires and gave the world Lenin, Stalin, Mussolini, and Hitler.

It was Britain whose capitulation to U.S. pressure and dissolution of her twenty-year pact with Japan in 1922 insulted, isolated, and enraged that faithful ally, leading directly to Japanese militarism, aggression, and World War II in the Pacific.

It was Britain's lead in imposing the League of Nations sanctions on Italy over Abyssinia that destroyed the Stresa Front, isolated Italy, and drove Mussolini into the arms of Hitler.

Had the British stood firm and backed Paris, the French army could have chased Hitler's battalions out of the Rhineland in 1936 and reoccupied it.

Had the British not gone to Munich, Hitler would have had to fight for the Sudetenland and Europe might have united against him.

Had Britain not issued the war guarantee to Poland and declared war over Poland, there might have been no war in Western Europe and no World War II. (414)

America is the last superpower because she stayed out of the world wars until their final acts. And because she stayed out of the alliances and the world wars longer than any other great power, America avoided the fate of the seven other nations that entered the twentieth century as great powers. The British, French, German, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, Ottoman, and Japanese empires are all gone. We alone remain, because we had men who recalled the wisdom of Washington, Jefferson, and John Quincy Adams about avoiding entangling alliances, staying out of European wars, and not going "abroad in search of monsters to destroy." (417)

With the end of the Cold War in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, America was at her apogee. All the great European nations—Britain, France, Germany, Italy—were U.S. allies, as were Turkey, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt in the Middle East, and Australia, South Korea, and Japan in the Far East. In the Reagan era, Russia was converted from the "evil empire" of the early 1980s into a nation where he could walk Red Square arm in arm with Gorbachev, with Russians straining to pat him on the back.

Four hundred million people in Europe and the USSR had been set free. The Red Army had begun to pack and go home. The captive nations looked on Reagan's America as their liberator. With all the territory and security any country could ask for, the first economic, political, cultural, and military power on earth, America ought to have adopted a policy to protect and preserve what she had. For she had everything. Instead we started out on the familiar road. We were now going to create our own New World Order.

After 9/11, the project took on urgency when George W. Bush, a president disinterested and untutored in foreign policy, was converted to a Wilsonian ideology of democratic fundamentalism: Only by making the whole world democratic can we make America secure. (420)

There is hardly a blunder of the British Empire we have not replicated. As Grey and Churchill seized, on von Kluck's violation of Belgian neutrality to put their precooked plans for war into effect, the neoconservatives seized on 9/11 to persuade our untutored president that he had a historic mission to bring down Saddam Hussein, liberate Iraq, establish a strategic position flanking Iran and Syria democratize the Middle East and the Islamic world, and make himself the Churchill of his generation. (421)

As Britain had a "balance-of-power" policy not to permit any nation to become dominant in Europe, the 2002 National Security Strategy of the United States declares our intention not to permit any nation to rise to a position to challenge U.S. dominance on any continent—an attempt to freeze in place America's transient moment of global supremacy. But time does not stand still. New powers arise. Old powers fade. And no power can for long dominate the whole world. Look again at that graveyard of empires, the twentieth century. Even we Americans cannot stop the march of history.

As Britain threw over Japan and drove Italy into the arms of Hitler, Bush pushes Russia's Putin into the arms of China by meddling in the politics of Georgia, Ukraine, and Belarus, planting U.S. bases in Central Asia, and hectoring him for running an autocratic state that does not pass muster with the National Endowment for Democracy.

Ours is a peculiarly American blindness. Under the Monroe Doctrine, foreign powers are to stay out of our hemisphere. Yet no other great power is permitted to have its own sphere of influence. We bellow self-righteously when foreigners funnel cash into our elections, yet intrude massively with tax dollars in the elections of other nations to promote our religion of democracy.

As the British launched an imperial war in Iraq after their victory over the Ottoman Empire, we launched a war in Iraq after our victory over the Soviet Empire. Never before have our commitments been so numerous or extensive. (422)

Like the British before us, America has reached imperial overstretch. Either we double or treble our air, sea, and land forces, or we start shedding commitments, or we are headed inexorably for an American Dienbienphu. (423)

America is as overextended as the British Empire of 1939. We have commitments to fight on behalf of scores of nations that have nothing to do with our vital interests, commitments we could not honor were several to be called in at once. We have declared it to be U.S. policy to democratize the planet, to hold every nation to our standards of social justice and human rights, and to "end tyranny in the world."

And to show the world he meant business, President Bush had placed in his Oval Office a bust of Winston Churchill. (423)

|