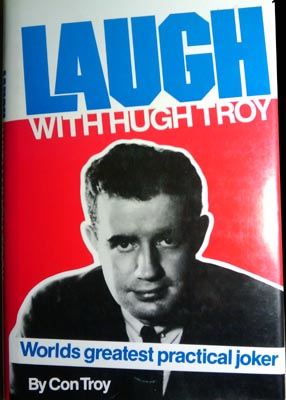

Laugh with Hugh Troy: World's Greatest Practical Joker

Con Troy (1983)

During summer vacation, Hugh's father and mother would leave for a few week's trip, part business, part pleasure. They'd leave the children—Elinor, Hugh's young brother, Francis, Edith, and Hugh—with Grandma. As soon as his father and mother left, Hugh would begin on Grandma by mixing up her calendar. She was fond of reading the  New York Times in the morning. Usually she would fall asleep by the third or fourth page. Hugh would then replace the paper with the one from the day before. If she fell asleep on Friday, when she woke up it would be Thursday. After doing this a few times, Hugh actually got Grandma to the point where Wednesday became Sunday to her.

New York Times in the morning. Usually she would fall asleep by the third or fourth page. Hugh would then replace the paper with the one from the day before. If she fell asleep on Friday, when she woke up it would be Thursday. After doing this a few times, Hugh actually got Grandma to the point where Wednesday became Sunday to her.

"Elinor!—Hugh!" she called to them on Wednesday morning. "Don't you know it's getting late? It's almost time for church."

"Yes, Grandma," they replied.

Then Grandma visited Nellie in the kitchen who was in on the scheme. "Nellie, are you getting the chicken ready for dinner?"

"Yes, Mrs. Troy," Nellie said. "It'll be ready when they come back from church."

The children dressed and left for a long walk and, after they came back, Hugh got out the Sunday papers which they had hidden for four days. Then they all sat down to dinner and Grandma led them in prayer.

It was harder to bring Grandma back up to date when the time approached for the return of Father and Mother. They had to shuffle the papers in reverse fashion. Still, they managed to do it Grandma was back on the same schedule as the rest of the world when the parents returned. (30)

Hugh Troy inspired his Cornell classmates to take a more relaxed view of life and use a little more fun to spice their daily existence. (31)

Hugh came home with the news that he and the other culprits had been ordered to appear before the faculty committee. The Troy's neighbor, Professor Fred Barnes, happened to be there. He was a member of the committee who was more broad-minded than the others. "Pin some mistletoe to the seat of your pants," he advised Hugh. "Then, as you leave the room, flip up your coattails." (52-3)

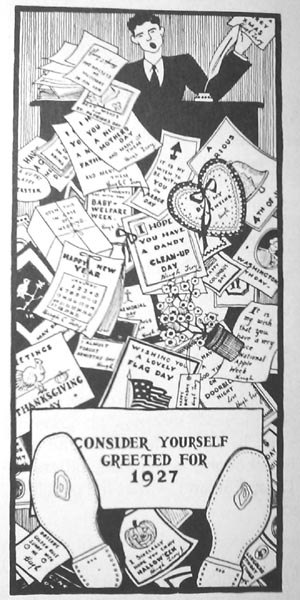

Hugh's New Year's card demonstrated his newfound ebullience. It represented his first satire on America's growing infatuation with greeting cards, more than covering all the holidays in the coming year, 1927. (53-4)

Living so close to the park, Hugh often strolled along its shady paths for relaxation. Sometimes, after lunch, he'd stretch out on one of the park benches and take a nap.

On a warm spring day, one of New York's finest, let's call him Flanagan, saw Hugh snoozing on a bench and proceeded to acquaint him with correct park bench etiquette.

Whack! went Flanagan's club against the sole of Hugh's shoe.

"Wha ... what's the matter, officer?" said Hugh, sitting up.

"Feet on the ground, Mac. No sleeping on the city benches."

Watching Flanagan stroll away, Hugh pondered the injustice of such a regulation. Then he smiled to himself, a very satisfied smile.

A week later, Hugh was snoozing peacefully on a bench when he got another hot-foot.

"Listen, Mac," said the lawman, "I've told you before. No sleeping on the city benches. 'Gainst the law."

"But, officer, I'm not breaking the law."

"Whaddya mean, not breaking the law?"

"Just what I said."

"Listen, Buster. You've had that bench long enough. Move along."

"No. This is my bench. I'm staying right here."

"Your bench, hey? That's the best one I ever heard. Okay. Stay right there a few minutes. We'll see what in hell's coming off here."

Ten minutes later, Flanagan and his buddy showed up with the paddy wagon. They ordered Troy into the wagon.

"Wait a minute, officer. Put the bench in, too."

"The bench? Why?"

"Because it's my bench. If that doesn't go, I won't go."

Impressed by Hugh's two-hundred-pound, six-foot-six frame, the bluecoats decided to humor him and took the bench along with Hugh to the station house.

"All right," said the magistrate whom the police called "the judge." "What do we have here?"

"Your Honor," said Flanagan, "I've warned this fellow every time I caught him sleeping on a bench in the park. Today he refused to get off and—"

"Is this true, Mister ... " The judge looked at the docket. " ... Mr. Troy?"

"Yes, that much is true, your honor. But I—"

"Stop right there," interrupted the judge. "Officer Flanagan gave you fair warning about sleeping on public property. You've admitted it. That's enough evidence."

"But, your honor, may I say something?"

"You've had your say. You admitted sleeping on a city bench."

"Oh, no, your honor. Take a look at that bench. It doesn't have the Park Department's initials on it."

"Doesn't matter. Anyone can see it's a city park bench."

"Well, then, what about this?" said Hugh, handing the judge a slip of paper.

The judge read it. It was a bill of sale for the bench.

Hugh had found the shop that made the benches and had bought one for himself. He and a friend had carried it into the park. Hugh had committed no crime. The judge released him. But that's not the end of the story.

Hugh realized that, because Central Park was dozens of blocks long, its various areas were patrolled by different policemen. The next day, he and his friend carried the bench a few blocks south and waited until they saw a patrolman coming. Picking up the bench, they started walking away with it.

"Hold it, boys. Where you going with that bench?"

"Why," said Hugh, "we're just taking it home."

"Oh, taking it home, are you? Well, drop it right there. I'm taking you in to the station house."

There, once again, the flabbergasted judge had to let Hugh go. And, instead of congratulating the patrolman, he dressed him down for having been taken in as a sucker.

Hugh tried it once more in another part of the park. That ended it, for the irate judge finally snapped out at Hugh. "Look Troy. This is your last trip in here with that blasted bench. If I ever see you with it again, I'll rip it apart and beat you over the head with the planks." (61-3)

[Many decades later this story was appropriated by Abbie Hoffman]

"People should be mystified more than they are," Hugh once asserted. "life moves along too regularly." (79)

That summer, fancying herself a patron of the arts, a rich and famous lady planned a benefit carnival and art auction at her estate at Sands Point, Long Island. Her affair was strictly by invitation, the only people to attend being the cream of the social register crowd. Commanding various artists, including Hugh, to volunteer their services, she asked them to bring their paints and brushes.

Arriving at her mansion, they were escorted into her lordly presence. "I'm giving you just two minutes of my time," she told them imperiously. "Your task is very simple. Each of you is to paint a picture for the auction. You'll find easels and various sizes of canvases and illustration board on the terrace. You may leave your paintings right there. Please get to work right now. My carnival starts in two hours."

"Will we be attending your carnival?" timidly asked one of the painters.

"Oh, no. Our caterers have more than they can handle now."

Hugh raised his hand. "May I ask—"

"No more questions please. I have too many things to do," she replied, flouncing out of the room.

Selecting four of the largest canvases, Hugh retired to a quiet corner of the terrace to paint. In short order he finished his task, but he didn't leave his works on the terrace. Carrying them down to the big stone gate beside a busy highway, he put them on display around the entrance to the estate. They were signs:

WELCOME TO THE CARNIVAL!

FREE RIDES! BRING THE KIDDIES!

FREE DRINKS FOR ALL!

PICNIC PARTIES WELCOME! (95-6)

The Post Office Department had just issued a new ruling that every RFD mailbox in the country had to display its owner's name. The sight of Hugh in his paint-spattered overalls (he was going to do a watercolor in the orchard) reminded his host of the new regulation. He asked if Hugh would mind lettering his mailbox for him.

"Sure," said Hugh. He ambled down to the lane entrance and was lettering away, chewing on a blade of grass, when a long, glossy car approached. With a shriek of protest from the tires, it shuddered to a stop. A pouter pigeon of a man slowly pulled a fat cigar from his mouth and called out, "Hey, bub! Yes, you! Whatcha charge for that job?"

The artist immediately became a yokel handyman. Pulling out the blade of grass, he poised it in midair.

"Pends," he drawled. "Letters so big fetch six cent apiece. I also got a eight cent letter. Fancier. I call 'er 'Little Beaut.'"

The man flicked Hugh a visiting card. "Like to do my box this afternoon? Just up the road. Second house on the right."

"Plain letter or little Beaut?"

The man grinned. "I'll take a chance on little Beaut, bub."

"Okee-beebee-dokie," said Hugh. Then he added quickly, "Hold yer hosses a minute, boss." He studied the name on the card, pausing to scratch his head and stare at the sky while his lips and fingers did counting exercises. Finally he had it worked out.

"Comes to a dollar thutty-six," he said. "Call 'er a dollar thutty-five even. Oke?"

"I think I can scrape up that much." And the long, glossy car moved down the road.

That afternoon Mr. Pouter was sitting on his terrace with his guests when a handsome new station wagon drew up at his mailbox below. A chauffeur, in whipcord and leggings, emerged and set up some beach chairs. Then a butler in a morning coat appeared, spread a luncheon cloth, and anchored it with an icebucket of champagne.

Now came a second station wagon, identical, bringing two incandescently beautiful girls wearing sunsuits, along with Hugh, still in his spattered overalls, still chewing grass.

The girls draped themselves in the chairs and accepted glasses of champagne. Hugh picked up a brush and a jar of paint. While the girls went "ooooh" and "aaaah" in admiration, he lettered the mailbox. Back on his terrace, the lord of the manor and his friends sat slack-jawed.

The job finished, the gangling handyman shambled up the terrace, performed an awkward bow, and said, "That'll be a dollar thutty-five, boss."

The landed proprietor handed it over. And now, the chauffeur and the butler packed up and the two station wagons departed, leaving the astonished people on the terrace to their own feverish conclusions.

Hugh couldn't resist a final touch. Two weeks later the owner of the artist's handiwork found, in his neatly lettered mailbox, a note on Hugh's letterhead. It said, "The Museum of Modern Art is preparing an exhibition of mailboxes I've done. Since I consider yours to be the finest example of my blue phase, would you be good enough to lend it?" (103-4)

For most New Yorkers, having a car has one disadvantage—no convenient place to park. But that didn't bother Hugh. He parked right at his front door next to a fire hydrant. (No one else would risk the huge fine for parking in such a spot.) He would then pick up the hydrant—a fake he had carved out of balsa wood—and hide it in the trunk of his car. (108)

The newlyweds' time together after the wedding was all too short. Soon afterward, Hugh was off to Connecticut for his induction into the Air Corps. Wouldn't you suppose that Hugh, with a background of dubious military value, would be tucked away in some obscure cubbyhole as a lowly buck private? Well, guess again. Here's Hugh:

I was inducted in a huge building near Hartford, Connecticut, and I recall those long lines, as far as you could see, of naked men, each clutching a brown paper bag that held an apple and a cheese sandwich. The food was to eat if we got hungry while going through the different booths. It was fascinating. I'd never been through anything like that before.

I finally entered a room with about eight desks. It was late in the afternoon so most of the men normally at the desks had gone home. At the last desk sat a man with three huge volumes that listed all the MOS (Military Operation Specialty) numbers in the service.

He also had a machine for punching IBM cards. He'd put your card in his machine, hit some buttons, and the machine would punch your card with your MOS number. Once he punched your card with that number, you were stuck with it, for life. That was the number that determined the course of your training and, thus, your whole career in the service.

"Which do you like best," he asked me, "to write or to paint?"

'Why, neither," I said. "I like 'em both."

"Well you have to tell me one so I can give you a number."

"I do 'em both well," I said, "and I don't want any of your numbers."

Well," he said, "I've gotta give you some number."

He stuck my card in his machine and was going to punch it for me. But just then the phone rang at one of the vacant desks and he left to answer it. While his back as turned, I reached over to his machine and quickly gave my card eight wild punches. As a result, according to my card, I was qualified as, of all things, a demolition expert!

Now, I've always been deathly afraid of handling anything like dynamite or TNT. But now they wanted me to teach it! And—would you believe it?—I wound up as a second lieutenant in the Air Force Intelligence School and was put on the staff! And those eight wild punches did it all. (117-18)

He soon became browned off at the avalanche of paperwork that fell on his desk every day. A good half of it was utterly futile, he told his C.O. He was learning nothing and getting nowhere, and his contribution to the war effort was a big, fat, empty zero.

His C.O. lived by The Book. "If Washington wants you to do this paperwork," he said, "you'll do it. Yours not to reason why. Surely you're not suggesting that a mere lieutenant knows more than the Chief of Staff of the Army of the United States?"

The operative word was "mere." It cocked a trigger which a gnat's weight—or a fly's, as it happened—could trip.

One August afternoon Lieutenant Troy was inspecting one of the messhalls. Though the summer was well along, window screens had not been issued. So the mess sergeants, to keep the flies down, had hung up half a dozen of those sticky flypaper spirals. Troy saw them and the trigger tripped.

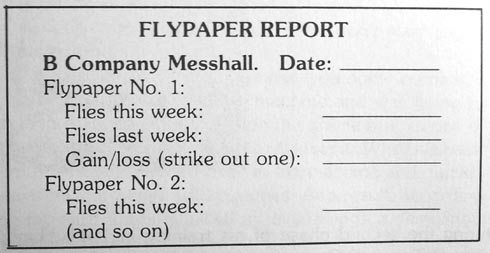

Back in his office, he conceived and drew up a form:

And so went the report for all six flypaper spirals. Then he ran off a sheaf of copies, filled in random figures on the top one, worked out the averages and the grand totals, and sent the form along with the weekly bundle going to the Pentagon, keeping a carbon for his files. His plan was to let the weekly carbons pile up for a month, then spread them in front of the C.O.: "See, sir, I told you nobody reads our gibberish!"

The month ended without an echo, and Hugh was gathering his carbons for the confrontation when a distraught lieutenant burst into the office. "You Troy? Thank God I caught you! I'm from A Company. Listen,what's all this about some Flypaper Report I'm supposed to turn in? The Old Man just got a rocket from Washington, asking why his Flypaper Reports weren't complete, and he's chewing out every adjutant on the base. I wouldn't know a Flypaper Report if it pinned a medal on me, but my clerk says he heard your clerk mention 'em. Brief me, will you?"

Troy reeled. With a feeling that he had sown the wind and someone was about to reap the whirlwind, he brought out one of his forms and explained how to complete it.

"Gotcha!" the lieutenant said. "Thanks!—but wait, hold on a minute! There's one thing here I don't get. You say 'flies this week' and 'flies last week.' When you check your flypapers, how do you tell last week's flies from this week's?"

A genius capable of the grand conception of the Flypaper Report was also capable of working out its details. "A very good question," Troy assured him. "You're the first one who has had the vision to ask it. The answer is,"—and it came to him at that instant—"I have a sergeant follow me around with a matchstick and a saucer of ketchup, and as I count each fly, he daubs it. Simple! No sweat at all. Some sergeants prefer mustard as a dauber, but we here in B Company find that ketchup has a certain something that mustard lacks."

The lieutenant glowed. "Well, I've got the pitch now. Thanks a million, chum! If it hadn't been for you, my wife would be addressing my letters, 'P.F.C.' "

He rushed out, almost colliding with a C Company officer, entering with one from D Company. It developed that they had to turn in some flypaper reports—or else; and what in the name of Robert E. Napoleon was a "flypaper report"? Troy sighed and reached into his drawer for some more forms. . .

From that day on, every bundle of reports that went to Washington included page after page of Flypaper Reports and, for all Hugh knows, the Pentagon made them standard procedure for all the armed forces.

Detached from the engineers some time later, Hugh never learned whether his whirlwind harmlessly blew itself out, or cut a swath of devastation. But as he left, he suspected that somewhere in the Pentagon there was a Flypaper Report Section, and that its C.O., a full colonel, spent half his time writing petitions in triplicate for "personnel increments" so that he'd be able to discharge his duties with the thoroughness their importance deserved. (119-23)

He wound up on Saipan with General Curtis LeMay's 21st Bomber Command, 20th Air Force, as an air reconnaissance officer. But his duties involved more than air reconnaissance. In Hugh's words:

I was with an advance party, just a few B-29's, on Saipan in the Marianas group where the island people were Chamorros. Most of them were loyal but we were a little leery of them, so we kept them locked up in compounds. Only the children were allowed outside.

We'd just got settled in there when this good-looking, tall, bearded man wearing U. S. insignia showed up. He was a civilian folklorist named Atherton from the Library of Congress whose job was to collect the legends of the Marianas.

He shouldn't have been there. His superiors must have been confused, however, and figured the islands were secure. But they weren't. So my boss, General Nichol, called me in.

"Captain Troy," he said, "we can't have this fellow here. Will you see that he gets whatever he wants? Then get him the hell off this damned island before he gets killed."

"Yes, sir," I replied. "I'll take care of him."

I talked to the folklorist and, lo and behold, learned that he had brought along seven quarts of whiskey. That was a smart idea on his part because whiskey was practically a medium of exchange. You could swap a quart or two for almost anything. I was interested because, being an advance party, we were on short rations. We hadn't seen liquor for weeks.

Every morning I had to drive to a little bombed-out town on the coast to bring in our mail. And on those trips I'd often take along a little Chamorro boy named Emmanuel who was allowed to leave the compound. He was a sweet little kid who spoke English, having gone to an American school. His parents having been killed in the war, he was living with his grandfather.

After I talked to the folklorist, I picked up Emmanuel as usual the next morning. I could see the makings of a deal.

"Look, Emmanuel," I said, "if I were to tell you some stories in English, could you tell the same stories in Chamorro?"

"Sure," said Emmanuel, "but why?"

"Well," I said, "he likes to collect stories. Now here's what I'll do. For every story you tell the gentleman, I'll give you three comic books and three Hershey bars. But you mustn't tell anyone else about it. And you must be sure to tell the gentleman that your grandmother used to tell you the stories before you went to bed at night. Okay?"

"Sure, fine," said Emmanuel.

So that took care of Emmanuel's part in my scheme. Then I wangled a deal with the folklorist. "Atherton," I said, "suppose I were to get a true local legend for you. Would it be worth a quart of whiskey?"

"Of course," he said. "But how can you get any legends?"

"Why, I have a friend," I said, "a little Chamorro boy who knows them. But he tells them in Chamorro of course."

"No problem," said Atherton. "I'll just bring my interpreter along."

"Okay," I said. "I'll set it up and let you know."

Every night after that my buddies and I would have a long bull session in our tent. We called our confab "The Children's Hour" and in it we wrote the legends of old Saipan. I cooked up a literary goulash using a portion of Aesop's Fables, a goodly gob of Mother Goose, and a dash of Winnie the Pooh.

Each time I picked up Emmanuel I'd teach him the story we'd dreamed up the night before. Then I'd go and get Atherton.

"Hop in, Atherton," I'd say. "We're going over to the compound."

He'd grab his interpreter and we'd all go over to the hut of Emmanuel's grandfather. The old man would sit on the floor smoking his pipe while the young fellow rattled off this tall tale I'd taught him. The interpreter would take it all down in shorthand while Atherton sat there beaming, simply thrilled at the way things were going. A couple of days later we'd do another story. This went on until I had all of Atherton's whiskey. He finally flew back to Washington with his marvelous collection of legends.

But one thing puzzled me: Every time we went through that rigmarole and Emmanuel had finished talking, his grandfather would spout a line of gibberish to him, all in Chamorro of course. So, after I'd got all the whiskey and Emmanuel was loaded up with comic books and Hershey bars, I asked the boy about it.

"Tell me something," I said. "What was it your grandfather said every time you finished telling one of those stories?"

"Oh," said Emmanuel, "he'd say, 'where in the world did you ever hear such a lot of horse manure?'" (126-9) [See also]

Back in his home in Garrison, Hugh, in his spare time, worked on solving a problem that had bothered him ever since he and Pat had moved in. Although their home was spacious, modern and afforded a spectacular view, it had one small drawback. It was directly across the river from the West Point Military Academy. So, at an unseemly hour every morning the dear, piercing notes of the Academy bugles would disturb their sleep.

Pat was reconciled to it. She looked on it simply as a disadvantage of living in that spot, something they would have to endure. She didn't know Hugh had a plan for abating the nuisance until she heard him talking to a clerk in a New York music store.

"Got any records of bugle calls?"

"Bugle calls? I'm afraid we don't have a thing like that in stock. But we could order it for you."

"Will it have 'reveille' on it?"

"Reveille? Must you have that?"

"Yes. You see, we live right across the river from West Point and their damned bugles wake us up every morning at six o'clock. I've got an amplifier and loudspeaker. And, as soon as I get that record, I'm going to blast them out of their bunks at five A.M."

"I pulled it off one morning," Hugh told a friend later, "and watched the effect through my binoculars. A line of men came streaming out of a building rubbing their eyes, but an officer herded them back in and pointed across the river.

"They got my message, all right. After that they toned their darned bugles down." (141-2)

He also told the group of the prank he played on President Truman's Secretary of State, Dean Acheson:

This incident took place, as I recall, toward the end of the Truman administration. Dean Acheson looks more like a Secretary of State than anyone else could ever hope to look. With his erect, military bearing, and bristly, sandy, adjutant's mustache, the Secretary was the prototype of the starch-straight, dignified, professional diplomat.

Dean and his children, who I knew quite well, didn't live far from my place. Their home was near a Presbyterian church on P Street that all the staid old Republican ladies attended every Sunday morning. Acheson didn't live there all the time; he had another house in the country.

One weekend it happened that the Secretary was at his country house. His children were in town, though, and helped me work this out. First, we hired a character actor of about Acheson's build. Then we togged him out in Dean's morning coat, his striped pants, his silk hat—the whole works that Acheson had to wear whenever he net a visiting dignitary at the airport.

So, on this particular Sunday morning, when the prim and proper old Republican ladies trooped by the Secretary's charming home in Georgetown, there, sitting on the front steps, was Dean Acheson in his full morning regalia, fishing. In a little pail of water.

His kids and I were sitting at a friend's house across the street, enjoying the show and especially the remarks of the passersby. As one group of dowagers slowed down to look at the spectacle with their mouths open, we could hear them saying,

"Dear, dear, isn't it sad?"

"Why, the poor man. He's off his rocker."

"Oh, my. They'll have to come and take him away." (161-2)

Bob Abbott: He dragged me to a Greenwich Village night club to see a short, fat lady coloratura who sang an involved operatic aria while she folded a huge sheet of paper into small squares and tore away bits of it with dramatic flourishes, all in tempo, until, at her grand finale, she unfurled a beautiful design in Spanish lace. He loved her! Night after night he went back to catch her act and to lead the applause, yelling, "Bravo! Bravo! Bravo!" (169)

Erling Brauner: One of Hugh's friends came home one night, opened his door, and snapped the light switch. A blinding blaze of light flooded the room which then went dark. Hugh had filled the sockets with flash bulbs. (170)

John Gatling: After my wife, Eleanor, and I had climbed to the top deck of a Fifth Avenue bus, I saw Hugh and a friend sitting up front. I wanted to hail him. But he was telling his companion a hair-raising story that had all the riders leaning forward, straining to hear him. Most of his words were low-key but now and then I'd catch a loud phrase like, "And then I bit her ear off." We left later without spoiling his act. (171)

Bob Mayers: In his talk to Cornell students in 1960, Hugh told how he entered a subway car carrying, under his coat, a false leg wearing a silk stocking and lady's shoe. After taking his seat, he slowly dropped the leg between his own legs. "It bothered nearby passengers so much," said Hugh, "that they got up and walked away." (172)

Herm Redden: At Cornell, Hugh was riding a bike in front of Willard Straight Hall when he spied a big sedan at the curb. Mama and Papa, followed by three young girls, got out, each one greeting in turn a freshman on the sidewalk, Hugh stopped, got in the car on the road side, crawled through and out, then shook hands with the astonished freshman. (173)

Hilda Berry Sanford: My father, Romeyn Berry, had arranged for Hugh to paint a scene on a large window in the Johnny Parsons Club, formerly on Cornell's Beebe Lake. One day,as a young girl, I was watching him at work. At his direction I changed the rolls on a player piano we were listening to. He complained, however, that the music sounded monotonous. So he had me unwind one of the rolls, rewind it backwards, and play it. It was a weird but refreshing change. (173)

One winter, no snow had fallen by Christmas eve so the Catholic church in downtown Ithaca was packed for midnight Mass. Hugh and a friend came in very late, with their hair and clothes covered with a half-inch of snow. They kept brushing it off as they stamped down the center aisle to a pew in front.

Murmurs of surprise and alarm ran through the congregation for many foresaw trouble driving back up to their homes on East Hill. But, when they left the church, they found the ground perfectly clear. Hugh had covered his friend and himself with artificial snow. (173-4)

Harry Wade: He nearly turned friends away from my wedding. He was one of my ushers and, as each guest came through the door, Hugh asked him, "Would you like a four or five dollar seat?" (174)

Edith Cueruo Zeissig: At more than one party the host would introduce Hugh to a guest. The guest would extend his hand and find himself grasping a large iron hook sticking out of Hugh's sleeve. "Glad to meet you," Hugh would say. "Pardon the hook." (174)

|