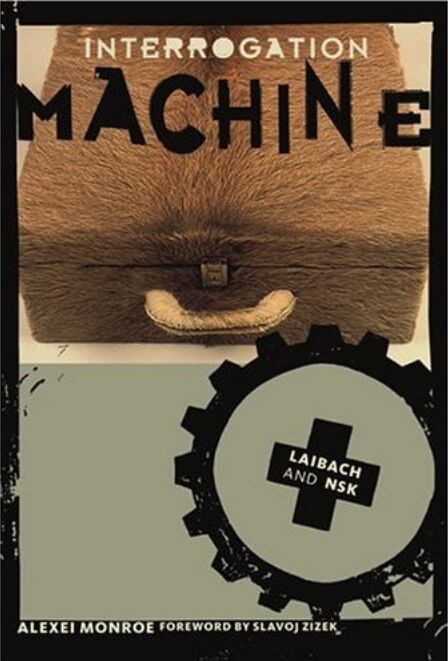

Interrogation Machine: Laibach and NSK

Alexei Monroe (2005)

[Many people will buy this book who want Laibach explained to them. After reading it, they may want Laibach to explain the book. There's no pleasing some folks. And there's probably no explaining Laibach. Monroe does a good job, anyway. Considering its subject, Interrogation Machine is appropriately murky. The act of reading it at some points nearly mirrors the effect of listening to trance music. I would think Laibach approve.]

The standard leftist argument against Laibach was a variation on the famous Groucho Marx statement: "These people talk like Fascists and act like Fascists; but this should not deceive you—they are Fascists." In short, things are what they seem: it is not appearance which occludes the hidden essence, it is the specter (semblance) of an essence hidden behind the appearance that occludes the truth of the appearance itself. Does this argument hold? The recent events encapsulated by the name "Abu Ghraib" point in a different direction. (xiii)

The explanation is the whip and you bleed. — Laibach

No apologies. This is not a conventional artistic biography, nor is it straightforward. NSK is a very dense and paradoxical subject, and engaging with it at the deepest levels means operating at a certain level of complexity. NSK's work is perplexing, traumatic, and contradictory. Producing a holistic view of the subject means not smoothing over or normalizing the tensions it produces. If the text is not always fully accessible, this is because its subject is not either, and to make it so would be to introduce dangerous simplifications of a type all too prevalent in the media and in politics. (Preface)

To understand the works and their contexts, it is important to perceive the oppressive density, coldness, and strangeness that surround them, and from which they are constructed. (Preface)

In effect, these processes represent a type of mystifying demystification executed via a type of (re)constructive deconstruction. This is apparent in Laibach's comment on the German group Einsturzende Neubauten: "The Neubauten are destroying new buildings and we are restoring the old ones. At this point we are replenishing each other." (11)

Laibach's work interrogates all authority mechanisms, and refers to the extreme social and ideological polarization and violence that have marked Slovene society. Laibach's severity is expressive of unresolved social tensions. (28)

It even published the document LAIBACH: The Instrumentality of the State Machine, a collection of early statements with an explicitly totalitarian tone. In effect. a state-subsidized institution published and subsidized material and activities by which the security and ideological arms of the state felt deeply threatened. (37)

Zizek insisted that the unassimilable surplus or "incredible core of enjoyment" in the NSK spectacle ultimately frustrates the attempts of both opponents and defenders to use NSK as a "point of suture" for their own narratives. (42)

In such works, Laibach in particular explored not only the fascination of trauma as a taboo, but the trauma of fascination. While this exploration owed a debt to the macabre conceptualism of Throbbing Gristle, or J. G. Ballard's explicit dystopianism, it was also concerned with illustrating the ambivalent status of fascination as such even while manipulating it. Laibach presented the abject and obscene but always had higher ambitions, and used rather than celebrated alienation. (47)

SYSTEMIC DISSOCIATION (OVER IDENTIFICATION AND DISIDENTIFICATION)

We are not nobody's appendages of nobody's politics—Tito/Laibach (48)

Laibach seem to take a delight in confounding the expectations they raise, either by including contradictory or ironic elements, or by disowning any possible connection to the tendency they have "sampled." (49)

Running alongside elements that are apparently deadly serious, and inextricably bound up with them, is a deep vein of black irony and absurdism. Laibach in particular are aware of striking ludicrous poses, and often use apparently trivial musical material, but this does not mean that everything is "really" a joke. Besides the militant strand of the avant-garde, there are also surrealistic and Dadaist tendencies at work, yet again these do not cancel out the very serious ambitions and the points being made, only qualify them and add to the complexity of the whole. (52)

In art, we appreciate humor that can't take a joke. [Laibach] (53)

Within NSK works and projects there are layers and levels of both concealed and overt meanings which audiences are left to uncover for themselves, and many of which may remain unidentified without chance discoveries of the sources. NSK statements are very often quotations, or collages of quotations, from frequently incompatible and rarely acknowledged sources. Some references will be fully understood only by those with specialist knowledge or a local connection; others will be completely missed, particularly those that refer to lesser-known artists and themes. (55)

The totalitarian motifs used by NSK are "retro," and in this respect absolutely contemporary given the popularity of "retro" styles and designs in postmodern culture. Posters, typography. and iconography from the socialist period are now commonly recycled in retro design both within the postsocialist zone and beyond. Although there is more obvious correspondence between these techniques and contemporary Western culture, the eclectic juxtaposition of imageries and concepts from different historical contexts is equally characteristic of the (post)socialist context. Epstein argues that Western authors have often overlooked the inherent postmodernity of Eastern totalitarianism, which in some respects anticipated Western postmodernism. (56)

As self-described "engineers of the human soul," Laibach can be compared metaphorically to scientists who consciously release harmful elements into the environment, on the grounds either that while they may be toxic they are not statistically dangerous, or that it is necessary for economic or scientific progress. However, just as the broad mass of both critics and consumers (and a great part of their audience) remain to be convinced of the therapeutic (as opposed to aesthetic or discursive) possibilities of Laibach's work, very frequently only the increasingly mistrusted scientists" themselves (often pretend to) believe in the safety, or the acceptable risks, of their work. The modernist faith in scientific progress that NSK reprocesses, however, is increasingly severely questioned, and perhaps because of this Laibach never seek to justify themselves except via intimidating theoretical language, and do not even try to pretend that they are concerned with possible unintended effects.

Laibach state at the end of the Bravo video: "Our only responsibility is to continue to be irresponsible"—meaning that Laibach have a responsibility only to their own principles and operations. Thus, although Laibach often claimed to anticipate at least some of the effects of their work, the reference to irresponsibility might be taken as a partial admission (which some contemporary scientists still cannot make) that experimentation with, or the manipulation of, volatile materials can have unpredicted and possibly undesired effects. In this statement about irresponsibility, Laibach preemptively shift the blame for any such problems to the nature of the materials themselves, for which they are not responsible but without which they cannot work. Even the peaceful (as opposed to consciously malicious) and controlled release of toxins into an environment can have bizarre and unpleasant side-effects, perhaps even for the scientists themselves, and there is also the constant danger of reprocessing operations going critical, or of undetected leaks. The more volatile the material, the more difficult and important it is precisely to calibrate a dosage which will be medicinal (homeopathic) rather than harmful. Most importantly, when a process is repeated in a new environment, the materials may well interact with the new context in a bizarre or dangerous fashion. (60-1)

Laibach's "right to incomprehensibility" expresses one of the clearest features of the group's work: a defence of ambiguity, and of the right not to have to explain every detail of an artistic process, or adopt clear political stances. Besides ambiguity, Laibach texts, images, music, and concerts also allow for simultaneity. The texts refer simultaneously to several sources and associations, and deliberately leave the resulting paradoxes to be resolved by the "consumer." (66-7)

Effective overidentification requires that suspicious evidence is not suppressed, but highlighted. Thus, presented with "the eternal question"—"Are you Fascists or not?"—Laibach responded: "Isn't it evident?" (79)

A jointly produced Irwin/NK Teddy Bear design (which was sold for charity in Ljubljana toy shops in 1995) demonstrated this new, more overtly playful strategy. The symbol of childhood innocence was problematized by a black-cross armband. The bear, Ursula Noordung, recurred in various works and installations, and was one of the more recognizable symbols of this phase of Irwin's work. (87)

In 1994 there was a performance for children (1:10,000,000), in which the young participants donned spacesuits to take part in a choreographed mystical scientific drama, complete with brutal electronic soundtrack and NSK symbolism. Adults were forced to watch the action lying prone peering down through a wooden cupola high above the stage. In 1995 came the premiere of Ena Proti Ena (One versus one), This Shakespeare-themed play by Vladimir Stojsavljevic has the theme of love and the state. It will be repeated in 2005, and thereafter each decade until 2045. As the actors die. they will be replaced by symbols, and in 2045 Zivadinov, the last living member of the company (although he is older than any of the other actors), is to be launched into space from Russia, and will complete the performance in zero gravity. (93-4)

Mlakar's most significant speeches in the 1990s took place in Sarajevo (1995) and Belgrade (1997); here the Bosnians were asked to conquer evil by forgiving their enemies, and the Serbs were asked to admit their guilt, and to be open to the possibility of forgiveness. These speeches echo the Department's most unambiguous mission statement: "Our mission is to make evil lose its nerves." (95)

In terms of low profile, NK and the other nonfounding NSK groups are actually closer to the abstract NSK paradigm of depersonalization, collective authorship, and anonymity than Laibach, Irwin, or Noordung. While texts by the three principal groups are always attributed to "Laibach" or "Irwin," members of these groups, and of Noordung, are frequently named, especially in the case of Laibach, who have been unable to escape the demands of a "rock" audience for information about members (to fulfill the audience's needs for identification as much as information), so that Laibach's spokesman is usually named in interviews, even though he is speaking for Laibach as a whole, meaning that the rule (or aspiration) of anonymity is often ignored in practice. Beyond the Slovene and Yugoslav press, however, the names of the individual members of NK are rarely referred to, although their identities are no secret. (103-4)

All three groups, especially Laibach, were known domestically, but were aware that a collective structure could generate a greater impression of momentum, and would be harder to ignore than individual groups known only within their respective "scenes." One advantage of the collective was that each NSK section was also constantly cross-publicizing the activities of the others, and of the whole, in a mutually reinforcing cycle. The "critical mass" this created was particularly important in achieving recognition beyond Yugoslavia, an objective held by the groups from a very early stage. (105)

Despite the impression of a tightly collectivist structure (seen in everything from members' public manner to the motifs, and even the names, of NSK groups), and the suspicions their work can evoke, NSK is not a "movement" but a core group of twelve permanent members, plus a much wider group of various collaborators, which actually operates more like a cottage industry or medieval community of artisans (an image NSK has alluded to) than the totalitarian combine or multinational corporation its image suggests. On paper, it is a highly regulated and formal body. Documents from the Internal Book of Laws, for example, are an intrinsic part of NSK's collective(ist) discourse. The Constitution of Membership and Basic Duties of NSK Members is deliberately reminiscent of the charters of medieval guilds and fraternities, and also evokes totalitarian depersonalization. These codes structure members' creative lives symbolically, and at the pragmatic level of group loyalty, but there is no formal supervision of personal actions. Since membership implies common perspectives and attitudes, there is no real necessity to abandon personal religious, aesthetic, and political preferences, as the regulations state—if a member held any that were truly incompatible, it would (have) be(en) pointless to apply for membership. Members voluntarily make a formal submission to the whole in awareness of the requirements of membership, many of which—such as fraternal respect, hard work and comradeship—are not so arduous for a group of enthusiastic and like-minded individuals. At some formal occasions, members greet each other ritualistically, but this, too, is an aspect of the collective performance. The entire NSK organizational discourse also represents a (paradoxical) exploration of and commentary upon the possibilities of working as a collective, both under self management and under late capitalism. (105)

This policy of confronting the state with its own desires via a hyperauthoritarian paradigm was also relevant in the West. France and Britain (even postdevolution) are more centralized than post-1974 Yugoslavia, and it is interesting to speculate how the British authorities might have responded to an equally extreme phenomenon. NSK's etatisme has the potential to touch the same raw nerves, both East and West. Challenging state authority is one of the most subversive of acts. The NSK example, however, suggests that when such a challenge is apparently based upon a more stringent ethos than that of the state itself, authority is nonplussed. (113)

This confidence made NSK's decision to launch itself as a global, nonterritorial state plausible rather than risible, and it has achieved greater impact than other similar projects. The structure provided a framework covering all fields of activity necessary to give a sense of completeness and self-sufficiency to the organization and the groups within it. Covering all foreseeable areas of cultural activity, and inscribing in its facade some of the trappings of an actual state, such as Economic and Technology "Assemblies," it predated by several years NSK's moves into areas such passports, currency, and stamps. (115)

Since only a small number of people have followed NSK since its inception, and perhaps not even the members themselves can detect every temporal inconsistency in later accounts of its history, it would hardly be impossible to doctor that history. This is especially true in the West, where information about NSK filtered through slowly via numerous—frequently rumor-laden—sources. There is no shortage of information concerning NSK. Since 1991 there have been several NSK publications containing increasingly accessible texts, as well as an immense quantity of foreign and domestic press material. Yet these are only now being synthesized into coherent chronological accounts, and this situation has enabled parallel (yet scarcely connected) accounts to survive, mutate, and proliferate. Therefore, NSK has little need for falsification, since these parallel and sometimes contradictory information streams, plus NSK's own mystifying pronouncements, maintain a space in which constant self-modification and alteration can always be synchronized with the facade, as in mutational totalitarian historiographies. Due to the plausibility of NSK's corporate facade, and the fact that it is not particularly concerned if anyone is perceptive enough to detect discontinuities, actual falsification (as opposed to dissimulation and concealment) is largely irrelevant. (118)

While NSK is passively secretive in deliberately keeping its own history relatively obscure, or at least never providing a full account of it, it simultaneously forces a new historical consciousness, both of its previously neglected sources and, implicitly, of the possibility that contemporary regimes (both local and foreign) might employ tactics of the type summarized by Gottlieb in her description of 1984: "In the long run, what the Party insists on is the demonization of historical time so that it can create a sense of its own timelessness.'" (119)

"By using the German language in the name NSK we do away with the debts that both the languages carry." [Laibach] (123)

The narratives of the Partisan period remained unquestioned up until the late 1980s, and to challenge them was a taboo as strong as the one that prohibited the use of the German name for Ljubljana. (123)

NSK was aware that a "purely" Slovene ethnic art would have little chance of attracting anything other than condescending attention in the West, and fully cognizant of the theoretical and aesthetic limitations of a self-consciously nationalist art that could never integrate some NSK elements, such as pop art or constructivism. NSK concluded that the only way to escape the "problem" of belonging to an obscure culture was deliberately to appropriate the strident and violent means by which external influences were imposed upon the Slovene space. The use of German in the name "NSK" confronted and directly acknowledged the decisive yet highly ambivalent influence of Germanic culture, consciously manipulating the sinister aura still attached to the language, while simultaneously adapting to Europe's single largest market, to which some Slovenes still feel closest politically and culturally. By using the language of their colonial overlords, many formerly subjugated peoples, above all the Irish, have had an influence upon English literature that is out of all proportion to their numbers. Such people use the language of the colonial "master" to force consciousness of the colonized "servant's" suppressed identity. NSK exposes the working of a similar Hegelian master-slave dialectic, acting with the very aggression employed by dominant colonizing cultures. (124-5)

It is important that a degree of ambiguity and paradox remains attached to the NSK structure, and that the NSK project can be read as if it were unambiguously nationalistic. Yet such a reading would also have to integrate the internationalist and cosmopolitan elements of NSK, as well as its use of irony and absurdity, all of which contradict the typical structures of nationalist ideologies. (125)

Laibach's very existence challenges the image of the Slovenes as wholly innocent victims of external aggression, and—in the language used to justify the ban on Laibach performances—"unearths disturbing memories" of collaboration and self-assimilation as much as external aggression. Laibach frustrate the wish to externalize violence and antidemocratic sentiment, and—when their presence among the Slovenes was acknowledged—to present them as the aberrant result of foreign oppression or influence. Laibach reanimated the threat of militantly antidemocratic forces: "When a rock band calling itself Laibach kitted itself in peaked caps, jackets and jodphurs, and barked songs about 'strong men of the nation' and so forth (often in German), it was evoking the Second World War, when the city was occupied by the Nazis for a year and a half. Open discussion of this period was taboo because it would have begged the question of fascist collaboration in wartime Slovenia." (126)

Laibach and NSK appropriated key "unspent" national symbols and reprocessed them. In the early 1980s such symbols seemed distant and quaint, and their unexpected reemergence had a spectral, uncanny quality. Even a folk symbol apparently as innocuous as the kozolec (Slovene hayrack) was "made strange" by Laibach's intervention. (130)

Laibach's first singer, Tomaz Hostnik, hanged himself from a kozolec. (288n24)

The widespread use of the German language and terminology in the works of NSK is based on the specific evocative quality of the language which, to non-German speakers, sounds decisive, curt, domineering and frightening, and automatically activates traumas buried deep in the subconscious and history. The activation of the Germanic trauma in turn activates the undifferentiated, unidentified, passive, nightmare-filled Slavic dream. (140)

Until the group reintroduced it into wide public circulation, the name-signifier "Laibach" was a de facto taboo word mentioned only in ritualized accounts of German oppression and wartime resistance. While it was never actually prohibited, such a prohibition would have been superfluous until 1980. Use by German nationalists or anti-Communist emigres could easily be dismissed, but the actual form in which the name reappeared was unforeseeable (particularly so soon after Tito's death), as was the extent to which "it" would penetrate national and international consciousness. It was not until 1983 that the legal status of the term ''Laibach" was defined, and this definition was based retrospectively upon an obscure local ordinance passed by Ljubljana City Council as recently as 1981. The lack of clearer provisions concerning Laibach's use was almost certainly due to its improbability, if not unthinkability. (158)

Laibach both suffered and benefited from the demonization of the alternative, most notably in the June 1983 "TV tednik" live interview with Jure Pengov, who played a role of willing provocateur similar to that of Bill Grundy in the infamous Sex Pistols interview of 1976. Laibach appeared in full uniform and armbands, with Laibach posters in the background, and recited "Documents of Oppression." Pengov upbraided the group for their use of German language and imagery at a time when the Slovene minority in Carinthia "have to fight for each word and sign"—a reference to Austrian nationalist groups' resistance to public bilingualism, even in majority Slovene areas of Carinthia. Although it later emerged that the interview was a case of mutual exploitation. Pengov nevertheless played the role of mouthpiece of civic repression, denouncing Laibach as "enemies of the people" and appealing to citizens to stop and destroy the group. (160-1)

Concerted official action against Laibach came only in response to the TV incident. In the immediate aftermath, the Ljubljana council decided that the use of the Germanized name was "without legal basis," and banned any future appearances in the city by the group under that name. During this period the name functioned as an absent signifier through its visual expression in the unnamed—effectively unnameable—black cross, which appeared on posters advertising Laibach concerts. and on the "anonymous" 1985 album. (161-2)

"We strongly reject all the accumulated controversy concerning our name and appearance leveled at us from some quarters of the Slovene public, although these arguments may be interpreted as a creative misunderstanding, which will be satisfactorily resolved in the future. Our name may be dirty but we are clean." [Laibach] (167)

The Laibach controversy has long faded, but Ljubljana's conflation with "Laibach," in both its historic wartime and artistic forms, is now indelible. An increasing number of visitors come to Ljubljana primarily or entirely as a result of the Laibach connection. Laibach postcards are sold from a stall by the statue of Slovenia's idolized national poet, Preseren, which in turn is overlooked by the same castle incorporated by NSK architects Graditelji into their designs for a monumental industrial city called "Laibach." For those Slovenes who are still disturbed by Laibach and what they represent, these continued reminders of the city's temporal and aesthetic displacement from itself are hardly welcome. A lasting symbolic consequence of Laibach's notoriety is that although Ljubljana is not better known as Laibach, it is certainly now much better known because of (its shadow) Laibach.

The continued symbolic appropriation (or "Laibachization") of Yugoslavia's first "hero city" and capital of the new republic reveals not only the continued symbolic-political impact of Laibach but also the shift in ideological and geopolitical alignment the city has undergone. (175-6)

The event created a minor scandal in the Slovene and Croatian media, and on May 12 Mladina published a letter from Laibach explaining its intentions in the concert; Laibach claimed that the organizers were fully aware of its content. The letter is one of Laibach's most open and detailed explanations of its methods (although the language retains the tautological and intimidating qualities of all Laibach statements). Laibach openly states that it is exploring "mass-psychology and the logic of manipulation through information," which would seem to confirm the worst fears of the group's critics (that for some obscure political purpose, or—perhaps worse—for the sake of pure provocation, Laibach practices mass manipulation). Laibach complicates this picture, however, through reference to the range of artists, schools, and ideologies that inform its "provocative interdisciplinary action"—for instance, Fluxus art and bruitism. (180)

Laibach's discourse is one of absolute certainty, and the stage performances are examples of absolutist totalitarian-style militancy. It is above all on stage that Laibach create a paradigm of impossible authority, driven by the iron logic of their concepts, manipulating audiences' desires to submit to overpowering spectacle even while challenging them. (184)

Laibach view Freddie Mercury as a highly successful politician able to command mass audiences. By exposing this totalitarian aspect, Laibach effect a postmodernizing archaicization of rock. The concerts demask and recapitulate a widespread penchant for or susceptibility to brutality, the persistence of (the desire for) Fascistic modes of identification and the decadent "state of the art" (commodification and personality cults). (186)

Laibach concerts both critique and participate in the institution of the live rock industry. A Laibach show amounts to a forensic presentation of the bloated—and, to some, decadent—apparatus of live music, including aggressive merchandising and audience depersonalization. This level of simulation, however, is necessary for practical as well as conceptual reasons. Laibach may seem to represent the institutional antithesis of the typical rock group, but since it operates within the (alternative) rock arena, all the usual promotional paraphernalia are functionally as well as conceptually essential. Since 1992, Laibach audiences have been confronted by a merchandising stall. Transactions carried out here form an important symbolic aspect of the show. Laibach use audiences to produce their own effects. Audiences consume ideologico-physical artifacts, subsidizing the operation and recapitulating the mechanics of the fan exploitation at the heart of rock. Laibach/NSK items such as stamps, ceramics, shoe-shine kits, NSK passport application documents, and literature are available as well as the more predictable T-shirts and posters. Profits from tour merchandising can far exceed those from record sales, and when these are produced by in-house designers the potential profits are even greater; however, since Laibach insist on expensive lighting and video techniques, merchandising serves only to subsidize tour expenses. The more unusual artifacts, such as ties and ceramics, are not cheap, but they are of high aesthetic/design quality. (186)

This hard core of the audience fall into two camps, both of which contain frivolous and deadly earnest members. To put it crudely, these are the ideological and the aesthetic. The latter are drawn by the image and the music, or their provocative and brutal qualities. The former—principally, but not exclusively, (preexistent) quasi-Nazis—are convinced that Laibach validate or approve of their beliefs. Both sets of fans share the conviction that their interpretation of and connection with the band or its work is both most valid and most intense. At Laibach's London concert in May 1992, there was an intense and potentially violent discussion between a group of left- and right-oriented Laibach fans which lasted for the duration of the show. The sowing of confusion and discord among the audience is indicative of the effects of Laibach's ideological and conceptual ambivalence—its apparent certainty creating doubt and multiple interpretations in the spectators. (188)

This discourse (which echoes Laibach statements) may be over the heads of many, but the speeches have a disciplining as well a symbolic function, consciously confronting limited attention spans and testing patience, in contrast to the usual hedonistic "surrender to the beat." (189)

Laibach's movements on stage are mostly cold, robotic, and relatively slow. The static remorselessness of the music and performers seems to fossilize rock conventions. Vocalist Milan Fras generally remains static and physically impassive. Normally the vocalist is the most mobile and animated performer, yet Fras makes only relatively slow, exaggeratedly theatrical gestures, such as a paternal sweep of the arm or a clenched fist. These gestures resemble the quasi-dictatorial gestures of Freddie Mercury. Fras's solemnity contrasts with the frenzied movements of demagogues such as Hitler, and is closer to the movements of Kraftwerk, Gilbert and George, and Joy Division's Ian Curtis. Fras rarely reacts either to the violence of the music or to the audience, short-circuiting the feedback of audience-band response. He seems to defy anyone to display more emotion than he does himself, while at the same time he is the focal point of a performance that deliberately whips up the audience. At his most severe he could be seen as embodying prohibition, or even as an overdramatized manifestation of a collective superego. In instrumental passages he simply stands motionless, looking straight ahead, indifferent even to the other performers, violently challenging all preconceptions of a rock performance, stripped of all expressiveness. The entire "classic" mode of rock performance is subjected to demonic parody. Rather than a charismatic "rock God" onto whom to project their fantasies, audiences are confronted by a cold Inquisitor figure embodying calm at the center of a storm. (190-1)

In presenting such material to German and Austrian audiences, Laibach exposed a whole new dynamic. The symbolic implications of a Slovene band with a taboo German name presenting images of Nazi atrocities as part of a highly Germanic and imperious performance using many totalitarian elements are vast. While they appear to be examples—if not advocates—of Germanic totalitarianism, they present graphic examples of Slovene suffering at the hands of such forces. The dynamic of a Slovene group traveling across Germany confronting audiences with such images, and using the type of arrogance postwar Germans were conditioned out of, is one of the most significant of any revealed through Laibach's work, indicating the complexity of their operations and the contextual subtlety behind what at first sight could seem like a gratuitous celebration of force and ritual. (193)

As Adorno pointed out, Fascist rallies contain a structurally ludicrous element, and NSK actions operate on a similar basis, on the verge of collapsing into their own contradictions. "It is probably the suspicion of the fictitiousness of their own 'group psychology' which makes Fascist crowds so merciless and unapproachable. If they would stop to reason for a second, the whole performance would go to pieces and they would be left to panic." (197)

As Adorno suggests. even the most primitive skinheads ("unstable individuals") live at a level of enlightenment sufficient to suggest to them that there may be something ridiculous about identifying with a man singing trashy pop songs as if they were masterpieces of Wagnerian opera, while wearing gold face paint and surrounded by antlers. (199)

When Laibach initiated their campaign of covering rock classics in 1987, this made explicit a process that had already begun: the creative re-exporting of Western ideas in the Slovene form of an ambiguously pluralistic assertion of national particularity, and the right to Slovene cultural self-confidence. (221)

Laibach described their cover versions as "new originals" (rather than hybrid forms or local imitations):

"The essence of music is a miracle of technology, which is based on mechanical principles of the universe. The essence of mechanics is Ewige Wilderkehr des Gleichen (Endess Repetition of the Same). On this basis we find no superiority in the cover-versions over sampling techniques. Our work, however, which is original, or rather a copy without the original, is superior to the historical material. (227)

Laibach's cover versions dramatized the extent of audiences' largely unconscious subjection in relation to rock and (particularly on NATO) suggested the danger of a pop-capitalist regime replacing the former Eastern regimes. In the case of Queen, subjects of Laibach's first cover version, Geburt einer Nation (originally "One Vision"), much of the work was already done, and almost no alteration of the lyrics beyond their translation into German was necessary to draw out Queen's authoritarian subtext. (228-9)

Laibach retroactively transformed One Vision into or revealed it as a Fascistic hymn to power, an effect amplified by the bombastic militaristic arrangement and harsh German vocal. The opening bars set a militant, uncompromising tone that creates the uncanny impression that the song is the natural expression of Laibach's Weltanschauung. The lyrics have obviously sinister connotations when they are sung in German by a group such as Laibach: "One man, one goal, one solution." After exposure to Laibach's intervention, Queen's song loses its innocence and apoliticality. Laibach are not ascribing any specific hidden agenda to Queen (beyond the conquest of new audiences and territories), but amplifying or "making strange" the structures of unquestioning adulation (and obedience) common to both totalitarian mass mobilization and capitalist mass consumption.

A key characteristic of this and many subsequent Laibach cover versions is that although the lyrical changes are often minimal, the new arrangements and change of context are so total as to create the impression that the tracks belong more naturally to Laibach than to their original authors, and that Queen and the other groups could actually be covering Laibach's "new originals." (229)

The album's title [Opus Dei] contained at least three levels of allusion. First, there was the (ab)use of the Austrian group's name. There was also the implication that Laibach's work was "The Work of God" (the literal Latin translation). Finally, there is a more sinister allusion to the quasi-Masonic Spanish Catholic sect Opus Dei, which has been associated with extreme right-wing activities. (230)

Kapital seems all the more obscure because the sleeve contains only fragments of the lyrics, as well as destabilizing esoteric phrases apparently unconnected to the tracks. Each album format (CD, tape, vinyl) contains a different sequence and alternate mixes of the tracks, heightening the sense of a multilayered, nonlinear "text" in which the playful, mystifying aspects of Laibach predominate over the militant and absolute. (236)

Laibach's archaic-barbaric manipulation of the German language makes it obscure even to native speakers. This cryptic quality recapitulates and toys with the fan's (and the researcher's) need to decipher lyrics. Besides this "Laibach Deutsch," The Hunter's Funeral Procession includes ritualistic Latin phrases provoking speculation about the secret meaning they "must" contain, The listener's belief that there must be some inherent meaning in the lyrics, and that at least some purpose will become apparent, is manipulated and enflamed. (238)

The album closes with Mars on the Drina, a punning rework of the Serbian nationalist tune Mars na Drini (March on the River Drina). (241-2)

The question is whether the group have gone beyond the mere documentation of these regimes, or whether their music has reached an "escape velocity" that enables it to transcend the limitations of its problematic source material. (244)

Laibach state: "In art morality is nonsense; in practice it is immoral; in people it is a sickness." (245)

Ambiguity is often codified by the media as "danger," and when Laibach loses the sinister associations of ambiguity, the group will have lost the transcendent menacing otherness that enables it to confront the regimes it interrogates. (245)

Since its totalitarian performance gives it the confidence to act in this way, there is no reason not to develop NSK statism to its (il)logical conclusion. The project totally ignores the laws of politics in positing a state without permanent territory, appropriating totalitarian arrogance and diverting it into cultural form, away from political forces that might wish to abuse it. This process echoes the "earthing" effect Laibach may have had within the Slovene political space, and is also an expression of political realities felt particularly acutely in Slovenia and Yugoslavia. (250)

The ultimate example of this is the NSK passport, an authentic simulation of the symbol of an individual's "given" (national) state identity. Responsibility for the use of NSK passports is placed on the bearers; they can be used as actual travel documents or kept as artifacts, but the extent to which they resemble "real" passports serves as an incitement to their use, especially for those who find their given statehoods problematic or inconvenient. The passports, manufactured according to international specifications, are described as documents "of a subversive nature and unique value." They have several symbolic meanings. They are the final codification of NSK's state aesthetic, and its artistic appropriation of processes normally reserved to state authorities. They also represent a materialization of the essence of all the NSK works that reprocess state motifs, and are both aesthetic artifacts and political documents. Their "subversiveness" lies not just in their symbolic appropriation of state power, but in their potential uses.

The most direct demonstration of their potential came during the 1995 NSK lriava Sarajevo event. The National Theater in Sarajevo was declared NSK state territory for a two-day event combining two Laibach performances, an exhibition, and speeches. Besides regular passports, a number of diplomatic passports were issued by NSK during the event. These documents, which were then used by several individuals to leave Sarajevo, play on the proliferation of new states in Europe since 1989, a context that provides cover for the appearance of yet another. The passports' authentic appearance and their "diplomatic" status proved a successful deterrent to close scrutiny by officials unfamiliar with the NSK State and its passports. (255)

There is nothing inherently democratic in the concept of "The First Global State of the Universe," which could equally describe a universal tyranny. Yet by claiming this role for itself, NSK has symbolically preempted and t(a)inted in advance the notion of a global state, pointing to the dystopian and utopian potential attached to the ideal. (257)

It is perhaps an example of the "nontotalitarian totality" envisaged by Epstein, and its nontotalitarian character is apparent in both its structure and its node of manifestation. The NSK State temporarily occupies specific physical locations into which it is invited, then moves on again. It needs no "repressive state apparatus" to maintain order, because the only territory it has to defend is conceptual. The NSK State represents the aestheticized spectacle of a total institution providing a safeguard for constantly threatened modes of freedom, particularly the rights to political and cultural ambiguity or nonalignment. (259)

The notion of a state contains its own uncanny excess, and Laibach's work and statements in particular dramatize this superrational quality: "The state was created by passion. We celebrate its creation with a feast where the tables are weak-legged under the weight of Fleisch [meat]. The Fleisch is the armour of reason." (260)

The logical culmination of NSK's manipulation of the emotions and energies associated with the state was the offering of citizenship. Many NSK passport holders have remarked that they feel happier with their voluntary status as citizen of a "state in time" than with their "given" national status, which often entails recognition of the dominance of a particular ethnic group or ideology by which the citizen may feel excluded or threatened. (261)

The state (a category currently under far more rigorous interrogation than the nation) has been appropriated by NSK and made into a non-hegemonic, aterritorial, "universal" structure which implicitly undermines established structures, and serves as a channel for identificatory drives which might otherwise go no further than teen euphoria succeeded by apathetic disillusion, or be transferred onto regressive sociopolitical forces presenting themselves as panaceas for the problems caused by alienation from the social, racial, or territorial status quo. (262)

The most effective example of this was the use of NSK diplomatic passports by besieged citizens of Sarajevo to escape the danger and suffering that their given political identity entailed. The device of art in the guise of the state opened up (albeit briefly) a symbolic space in which it was possible for individuals physically to transcend the increasingly sophisticated control systems that regulate movement across frontiers. It is true that these are only utopian "moments" affecting a few individuals, and that the regimes in question soon redeploy, yet they are utopian precisely to the extent that they are momentary, since in the present conditions at least, practices that are institutionalized cannot by definition remain utopian. In these actions, art has repeatedly leaked into the surrounding reality, generating tangible effects and demonstrating that the symbolic and philosophical implications continue to proliferate. NSK makes no attempt to marshal its citizens into a concrete force, and the state is not supportive of any literal "movement." However, when the implications of the self-bestowal of "diplomatic" status and the evasion of state control systems are considered, they do show that NSK has made breaches in otherwise monolithic regimes, and that its artistic praxis retains a countersystemic potential of a type rarely found in contemporary culture. These interventions suggest that regimes can successfully be confronted with their own hidden codes, disrupting normal functioning and opening up spaces in which it may be possible at least temporarily to resist and frustrate dominant ideologies by reprocessing them. (264)

In 2003, Laibach returned with the album WAT, at a moment when many people assumed or hoped that Laibach had finally fallen silent (similar feelings surrounded the group's return in 1992, after another quiet period). In the interim years, what might have seemed like excessively apocalyptic predictions on Laibach's part have been put into a new light by events. The advent of terrorist fundamentalism, neoliberal authoritarianism and interventionism, and "theocon" militarism and totalitarianism have left little ground for complacency. Laibach's "warning songs" seem both more appropriate than ever, and in constant danger of being overshadowed by events. (267)

During the Cold War, the short-wave frequencies were filled with obscure coded transmissions by the covert agencies of both sides. The end of the Cold War has not seen any reduction in such transmissions, any more than there has been a "peace dividend." Like one of these "numbers stations," Laibach have continued to broadcast both overt and covert codes. The "delayed-action" effect of the group's interventions means that the significance of some of its signals may not become apparent until long after their emergence, and they may activate "sleeper units" already at large in their host cultures. For the present. Laibach continue to scan the airwaves for faint signals of the future to make into the sound of things to come. (267-8)

Its effects still proliferate, and future events and trends will continue to suffer from comparison with or interrogation by Laibach. Even when Laibach ceases operations, the signals will continue to reverberate—Laibach continues to transmit. (268)

One of these possibilities would be to view NSK operations as a type of "cultural hacking," manipulating the source codes of various systems and inducing their inherent dysfunctions. Moreover, NSK is effectively restoring deleted data that would otherwise build up and compromise efficiency. Another possible technical metaphor would be the NSK Interrogation Machine as a culture oscillator, recording and generating signals from shifts between cultural poles.

Finally, NSK's work can be seen as a type of encrypted culture, protected by layers of ambiguity and misleading static. It has become clear over time that NSK's body of work is also partly an assertion of the right to remain ambiguous, and the right not to be defined or categorized. In an age of "total information awareness" and the systematic monitoring of individuals, an encrypted mode of culture and communication becomes not only valuable but essential.

If current political and cultural trends continue, total transparency might be achieved on the surface, but (with luck) it will never be possible entirely to monitor the most esoteric, recessed, and deepest aspects of culture and thought. Cultural mystery, secrecy, and ambiguity have to be preserved, since freedom and spontaneity reside in such shadowy, nondetermined spaces. In this context, we can say that cultural obscurity works as an illumination of the forces that demand constant total surveillance and accessibility. A key slogan of hackers and anarchists is "Encrypt and Survive," and this is equally valid for culture. Encryption, the reproduction of obscurity, is a means of preserving autonomy. In the relation between state and individual, one of the key questions is becoming: Who is allowed to make what visible?

The business of the individual (or of the artist) now has to be totally transparent to the state and its supporting corporations, but this is absolutely nonreciprocal. The state's "right to know" has no limits, whereas the citizen's "right to know" can be ever more constrained under a "permanent state of emergency" and officially manipulated panic. The raison d'etre or raison d'etat of artists such as NSK is to reveal what authority wants concealed (everything), and to conceal what authority wants revealed (everything). One of the key values of this approach is the ability of NSK works to hold together, and slow down and make visible all these contradictory forces we are structured by and exposed to. In effect. NSK works as a type of ideological time-lapse photography through which we can observe power and history in motion. By continuing to slow down the accelerating flows of culture and politics, NSK may be able to maintain and defend a space within which it remains possible to render perceptible the underlying noise and shadowy forms of power. (269)

+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=

[From the notes:]

+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=

At least thirty-two separate Slovene dialects are spoken, some of which are extremely impenetrable even to other Slovenes. (272n3)

Many NSK projects discreetly acknowledge external artistic collaborators and "guest" critics and academics have often contributed to NSK publications. In contrast, the sources of NSK works often remain unnamed and unknown, and are often given only because of legal requirements, not out of a desire to credit the original source. In the context of Laibach's "copies without originals," the specific identity of the individuals responsible (as opposed to their genres or associations) are of lesser importance, or even irrelevant. Asked about the source of a work, they will acknowledge an accurate detection but rarely volunteer information. "LAIBACH excludes any concept of the original idea," and see no need to acknowledge the specific source(s) of every image, particularly since the resultant uncertainties maintain audience speculation and fascination. Ramet's characterization of Laibach's work as "thought-energizing art" implicitly refers not merely to the aesthetic complexity but also to the effort required to track down the sources of the images, and process their implications. (279n58)

Interestingly, when Irwin applied for cultural funding for the NSK Embassy Moscow, the application was supposedly turned down on the basis that at that time, Slovenia could not afford to support its own state embassy. (284n64)

American artist Charlie Krafft, who has collaborated with NSK, had his NSK passport confiscated by Customs officials on his return to the USA, even though he had not attempted to use it to gain entry. (285n86)

[Re:] H. J. Syberberg, Hitler: A Film from Germany (Germany /UK/France: WDR/BBC/INA, 1977). The fact that one Laibach video is entitled Laibach: A Film from Slovenia, plus visual and other references in their work and in Predictions of Fire, illustrate the film's relevance to and influence upon the Laibach/NSK aesthetic. Like Laibach, Syberberg has been criticized for fostering an apparent nostalgia for traditional Germanic traits that the Nazis are seen to have tarnished irreparably. (290n55)

Laibach's music is frequently described as Wagnerian. (290n56)

Ironically, in reality Laibach are by no means fluent in German. (290n61)

[Re: Laibach's tour Die erste Bombardierung uber dem Deutschland (The First Bombing Over Germany):] The fact that the title is grammatically incorrect makes it seem even stranger and more alienating. (290n62)

The Germanic element in Laibach's work declined sharply after the release of Kapital (1992), and largely disappeared from the work of the other NSK sections. Its peak was roughly 1985-89. (291n65)

Beuys used these materials in his 1965 action How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare. Beuys smeared his head in gold and honey, as did Laibach's singer at the "illegal" Ljubljana concert in December 1984. Irwin used the same materials in some pieces. and Laibach also used a hare in some early performances. (298n31)

The appearance of graffiti was one of the most visible symptoms of the spread of Punk into Slovenia, and both Tomc (Druga Slovenija) and Erjavec and Grzinic (Ljubljana, Ljubljana) stress its importance. The appearance of foreign slogans and band names on the walls of Ljubljana was also a precursor to Laibach's "making strange" of the city. (300n26)

Symbolically, the Beatles had already introduced military elements into rock. Friedrich Kittler claims that they recorded secret messages on their albums using tape machines used on Second World War military decoding equipment. See Friedrich Kittler. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, trans. G. Winthrop-Young and M. Wutz (Stanford: Stanford University Press), 283. (303n90)

[NSK State] Application forms stipulate only that citizens should not bring the State into disrepute. (305n20)

|