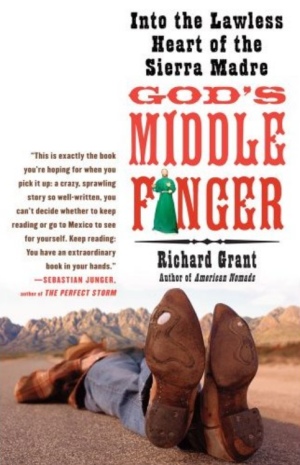

God's Middle Finger: Into the Lawless Heart of the Sierra Madre

Richard Grant (2008)

"You say you're alone and unarmed," said the short fat one. "Aren't you afraid someone will kill you?"

"Why would anyone want to kill me?"

The tall one smiled and said, "To please the trigger finger."

The short fat one smiled and said, "Someone could kill you and throw your body down a ravine and no one would ever know."

I should have grabbed that warm fleece-lined corduroy shirt when I bolted away from them into the forest. I can keep running and hiding all night but we're high up in the mountains, at eight thousand feet or so, and I'm already shivering in jeans and a T-shirt and by dawn the temperature will be close to freezing. (2-3)

From Joe Brown's front yard the foothills of the Sierra Madre are ninety miles away. He used to fly down there in a Cessna, back in his cattle-buying and gold-prospecting days, and he is still renowned in the town of Navojoa, Sonora, for buzzing the roof of the local whorehouse while flying drunk. On the second pass, with his favorite whore beside him in the passenger seat, he managed to knock off the TV aerial so the madam could no longer watch her soap operas. (7)

When the king of Spain asked Cortéz to describe the geography of Mexico, the country he had just conquered, Cortéz is said to have crumpled up a piece of paper and thrown it down on the table. (8)

The Sierra Madre Occidental was the last refuge for the Apaches, some of whom were still living free and raiding Mexican homesteads into the 1930s. (9)

My language school in Guanajuato had left me completely unprepared for his accent, which was slurred and grunted and composed almost entirely of gutturals. The letters s, t, d, n, b, and v were all gone from the alphabet. Buenos días, for example, sounded like weh-oh ee-ah. This was the accent of the northern Sierra Madre, as I came to discover, and I still wonder if it stems from generations of toothlessness. (29-30)

Ruben and I stayed up talking about the elusive, confounding nature of truth and facts in Mexico. A writer friend of mine called Chuck Bowden suggests that all events in Mexico go through three stages. First there is the event. Then there are the rumors and theories about what happened. Then comes the final stage. It never happened. (34)

During prohibition, Mexican smugglers known as tequileros would pack their mule trains with cases of tequila and send them across and down and over the border. Now the contraband was marijuana. (38)

As I swung aboard the saddle I remembered something Joe Brown had told me: "The horse is a noble animal who performs his service with grace. A mule will wait his whole life for the opportunity to kill a man." (39)

In 1885, in response to growing pressure from the U.S. government to abandon polygamy, the Mormon Church dispatched several hundred colonists to northern Mexico to extend the Mormon empire and continue to practice polygamy undisturbed. President Díaz was happy to sell them big tracts of land and unruffled by their marital practices. "It makes no difference to Mexico whether you drive your horse tandem or four abreast." (54)

Until the early 1980s, the people of the Sierra had been subsistence farmers and ranchers, growing or making everything they needed. Then the narcos from Sinaloa arrived in their big new trucks. They started buying up the private ranches in the area, paying in cash, and they had a stock response for the ranchers who refused to sell: "Very well then. I will buy the ranch from your widow." (57)

"I've never had any trouble with the drug people, just the ones pretending to put a stop to it. If they're up here looking for drugs, why don't they ask me for help? I can take them right to a couple of the big narcos around here and then we'll see if they still feel like throwing their weight around. Those federales will be out of the mountains right behind us. They'd never stop a vehicle after dark in the Sierra Madre. Then they might be forced to do what they're pretending to do and they'd be in real trouble." (94-5)

He doesn't want his real name in print because his life requires certain amount of illegal activity, such as failing to report treasure finds to the authorities, dodging taxes, and smuggling antiquities across the border. For the sake of convenience I'll call him Bill. He lives in a small house in Tucson crammed to the rafters with arrowheads, bones, Indian artifacts, nuggets of gold, chunks of precious gems and minerals, complete sets of five different treasure-hunting magazines dating back to the nineteenth century, and lots of old gold and silver coins. "The mistake a lot of treasure hunters make is they get fixated on gold. When I'm hunting treasure, I'm looking for shapes, forms, colors, a glint, anything that breaks the pattern of how that land would look undisturbed. A linear depression in the ground, a game trail. My eyes are going crazy trying to take it all in and my brain is whirling trying to categorize it all. I tell you, man, it'll take your mind into a different dimension." (95)

Some of the narco slang I knew. An AK-47 was a cuerno de chivo, a goat's horn, a reference to its curved ammunition clip. Colas de borrega, sheep's tails, were big, fluffy buds of marijuana. Ganado sin garrapatas, cattle without ticks, was marijuana without seeds. Cocaine was perko, parakeet, because it made you chatter without knowing what you were saying. Marijuana, especially in joint form, was gallo, the rooster, and heroin was chivo, the goat. All these terms, now in general use throughout Mexico, reflect the origins of the Mexican drug-smuggling business in the rural backcountry of the Sierra Madre. (112)

The young ones wore their hats with the sides curved up so high and tight that they pressed in against the crown— a style known as cinco en troka, five in the truck, meaning the crown of the hat is squeezed in as tightly as five people sitting across the bench seat of a pickup truck. (119)

"We are good people in Guirocoba but we have big problems with the fucking army right now," said Jaime, the older brother. "If anyone gives you problems there, tell them you're a friend of Jaime B and that he speaks for you."

This was no small matter. If my visit was connected rightly or wrongly in the suspicious minds of the outlaw clanfolk with some future bust or raid, Jaime would be held responsible and he could be killed for it. When you vouch for someone in a Sierra Madre drug village, you vouch for them with your life. So why did he do it, on such a casual acquaintance? Maybe because I knew a family name in his village. Maybe because he was feeling in an airy, expansive mood after drinking for thirty hours. There is always this tension in the Sierra between suspicion of outsiders and the urge to show hospitality toward strangers, and I seemed to have tapped into the latter. It was the opportunity I had been waiting for: safe passage into a notorious Sierra Madre drug-growing village. (121)

The institutions of government were too weak and corrupt and the market forces were too strong. There was a demand just across the border that created fifty billion dollars in profit every year. Illegal narcotics was the third-biggest industry in the world (after arms and oil) and the only conceivable obstacle to its profits—America legalizing drugs—was a political impossibility. (130)

It seemed to me that the surest way to make things worse in Mexico was to try to improve them. For example, there had been a recent campaign to curb the endemic criminality among Mexico's police officers. In Mexico City, Ciudad Juarez, and elsewhere, hundreds of police officers had been fired for corrupt and criminal behavior. It sounds like a sensible idea but it had created a crime wave. Shorn of their badges and released from the web of patronage that kept them answerable for their actions, the corrupt, predatory cops were not enrolling in architecture schools or starting up Internet cafes. They were plying the only trades they knew—extortion, theft, assassination, kidnapping, drug trafficking—with an even greater ferocity and ruthlessness than before.

The Zetas were another example, although this one couldn't be blamed on the Mexican authorities. This was the U.S. government's doing. At the School of the Americas in Fort Benning, Georgia, the U.S. Army trained an elite unit of Mexican paramilitaries called the Airborne Special Forces Group and gave them the firepower, helicopters, and other equipment to go up against the heavily armed and defended drug cartels. In the late 1990s they switched sides and started working for the Gulf cartel, using all their training and equipment to break drug lords out of high-security prisons, guard and transport drug shipments, and assassinate their rivals, along with various troublesome police chiefs and journalists. (131-2)

Regarding Chapo Guzman's escape from a different prison in a laundry basket, the article noted that "to the dismay of many law enforcement officials," escaping from prison is not a crime in Mexico, so long as the escapee doesn't hurt anyone or steal anything in the course of escaping. A Mexican Supreme Court judge explained the court's position with immaculate Mexican logic: "The person who tries to escape is seeking liberty, and that is deeply respected in the law." (143)

Within their families Guarijios are apparently quite chatty but it's not their custom to get together with the neighbors and swap stories around a campfire. Howard Scott Gentry, an ethnobotanist who made three trips among them in the 1930s and wrote the first and most thorough ethnography, said they were the most solitary and antisocial people he had ever heard of. (149)

"There are many bad men around here," she said. "A girl needs a pistol." (153)

Mexicans no longer use the word bandido for bandit. Bandido is now reserved for corrupt politicians and officials. For highway robbers or road agents, at least in the Sierra Madre, they use asaltantes (assailants) or gavilleros (members of a bandit gang). (156n)

"Wait a minute," I said. "My little Toyota has a small engine with four cylinders. You have a one-ton truck. Look how steep the road is. My truck can't pull you up that mountain."

He exhaled impatiently and his eyes turned steely. He pulled the gun out of his waistband and made a show of removing the clip and sliding it back in. He pointed it up at the sky, sighted along the barrel, stuck the gun back in his jeans, pointed to my Toyota with his chin, looked me dead in the eyes and said, "Yes it can."

"Okay," I said. "Andale pues, let's give it a try."

I felt oddly liberated and removed from myself. Responsibility for my actions was no longer mine. There was nothing I could do except obey the man with the gun. (161-2)

I stepped outside for a walk and there in the plaza was a man arranging small plastic jars into pyramids on a blanket. On closer inspection I saw that the jars contained rattlesnake oil, rattlesnake oil with bee venom, powdered rattlesnake, shark cartilage, coyote fat, and "bull extract." The man also had bars of soap that claimed to be made from a hunchback's hump, with a drawing of a dancing hunchback on the label.

I knew that hunchbacks were considered lucky in Mexico. I knew that people paid money to rub their humps for luck and that every hunchback in Mexico was assured of making a living in this way if he or she wanted to. But hunchback soap? Were these live or dead hunchbacks getting drained of their hump fat by the soapmaker? It was far too weird to contemplate and I assured myself that it was normal everyday soap with a fraudulent label. (180)

Before you start scoffing at Mexican folk remedies, let me remind you that you should also be scoffing at the five best-selling herbal or alternative medicines in the United States—saw palmetto (for prostate health), Saint-john's-wort (an antidepressive), echinacea (defense against the common cold), ginkgo biloba (memory function), and glucosamine chondroitin (joint health). In the first large-scale double-blind trials that they have been subjected to, at the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, all five of them were found to be completely ineffective. Yet I know many people who swear up and down that these medicines have helped them. My feeling is that we can persuade ourselves of absolutely anything, from the efficacy of snake oil to the existence of God, and that the world is a more interesting place because of it. (181)

First he took me down to lower Témoris. It is in effect a split-level town with two different microclimates. I was staying in upper Temoris, where pines and apple trees grow. Lower Témoris, four hundred meters down into the canyon of the Septentrión River, was semitropical with lush vegetation and banana trees. "In upper Tómoris, the people are colder, more reserved, more indifferent," said Baldimir. Down here, the people are hotter. They fuck and fight more. They dance and laugh more. It is the tropics." (185)

Sexually you would be surprised. There is no shortage of sex here but it's only sex. Afterward they don't know you and the next day it never happened."

Then he dropped a bomb into my brain. "Many narcos are bisexual and they are my specialty, you might say. At a certain point in the night, with all the drinking and cocaine, another side of them comes out. And they're risk-takers by nature. They don't expect to live long and they will try anything. You know there is an active and a passive position in homosexual intercourse? Well the narcos are always passives. Always, always."

"How interesting. Why do you think that is?"

"I think it's the eroticism of reversal for them. Normally they are the chingón, the one screwing-over other people, the hombre muy macho, and it excites them to turn the whole thing around."

"In Parral there's a famous gay narco who dresses all in pink—pink hat, pink jeans, pink boots, pink cowboy shirt. He goes to nightclubs with all his cute young boyfriends and he is greatly feared. But he is the only purely gay narco I know about. And I will bet that he is activo in bed. The others that I'm talking about have sex mostly with women, but they have this other side to them and I know about it very well." (189)

This was an unforeseen facet of Mexican machismo but in general I was growing very tired of it. At first it seemed amusing and outlandish, the way they growled and swaggered and cursed and talked about their testicles and each other's mothers all the time. Nowhere in the world had I encountered men more fixated on either subject. The bus driver between Creel and Batopilas, I remember, had a separate wife and family at both ends of his route and a withered bull's scrotum hanging from his rearview mirror, which he would stroke for luck before swinging the bus around the next hairpin curve.

Then it got wearying, the constant crude sexual bantering and self-aggrandizement of the macho, his contempt for women, his bristling pride and enjoyment of violence, his needless cruelty to dogs and horses and livestock. What I didn't know, mainly because machos were so touchy about other men being around their women, was the female perspective on all this but I made some headway the next morning. (190)

I didn't know what I was going to do about Sinaloa. I had no contacts there. Even on the map it looked sinister and forbidding and far too close for comfort. Just across the state line from Chihuahua was a village called Mátalo, which means Kill Him. (195)

The Jesuits followed them, built more missions, and succeeded in converting some Tarahumaras to Catholicism but by "withdrawal evasion, deceit, dissimulation, feigned ignorance and slander," as Susan Deeds characterizes it, most Tarahumaras resisted conversion and maintained their independence as a people. They would give Jesuits permission to come and talk to them and then be gone at the appointed time. They would refuse to answer questions or engage in discussion, and then state flatly that they wanted to go to hell, not heaven, They mocked the padres, saying celibacy was just a cover story for their impotence. They would try to goad them into fighting by throwing rocks at them and insulting their manhood. And thanks to the geography of the Sierra, there was always a backcountry hinterland where Tarahumaras could go and live as they pleased. (200)

What the Tarahumaras have always wanted is to be left alone by chabochis. That is what they call us—Spaniards, mestizo Mexicans, Anglos, non-Indians in general. The word refers to our facial hair (Tarahumara men are beardless) and the fact that we are children of the Devil. We are greedy and quick to violence, and we create disharmony wherever we go. It is best to avoid us and we can't be trusted but there's no point hating us. We can't help it. It's not our fault. We didn't ask to be fathered by the Devil. (201)

The first firecrackers of Holy Week exploded overhead, the lechuguilla was passed around, and that was the first time I heard the most Mexican of all drinking toasts: "El hígado no existe!" The liver does not exist! (208)

Their guide was a bullish cowboy type called Doug Rhodes who owned the lodge at Cerocahui, ran horse trips, and had been coming here for Semana Santa for many years. "No one here really knows what this means," he said. "It's just what they do and it's different every year because they were all too drunk to remember what they did last year. Have they brought out the dead baby yet? Some years they do. Some years they don't. It gets even wilder in Guapalaina." (221)

[Chapter title:] Sons of Obscene Perpetrations (224)

I had the feeling that taking peyote with the Tarahumaras, way out there in the high wilds of the Golden Triangle, would either be one of the crowning experiences of my life or reduce me to a gibbering wreck. (224)

Leaving Paral, we passed Randy's favorite local landmark: a children's amusement park built around a narco plane that had crashed outside town. (230)

We drank four or five gourds each and got nicely buzzed there on the rim of Sinforosa Canyon and it occurred to me that this was more or less the moment I had been looking for when I set out on his journey. Here I was in the heart of the Sierra Madre, about as far from consumer capitalism and the comfortably familiar as I could get, drinking tesguino with a wizened old Tarahumara and feeling that edgy, excited pleasure in being alive that follows a bad scare. It was an uncomfortable realization. To put it another way, here I was getting my kicks and curing my ennui in a place full of poverty and suffering, environmental and cultural destruction, widows and orphans from a slow-motion massacre. I tried to persuade myself that I was going to write something that would make a difference and help these people, but my capacity for self-delusion refused to stretch in that direction. (241)

According to Mary Jordan of the Washington Post, fewer than 1 percent of rapes are reported in Mexico, because it is not treated seriously as a crime and because rape victims who do go to the police are usually mocked and blamed for inviting the crime, and are sometimes raped by the police, who get aroused hearing the victim's story. (244)

In the Sierra Madre the practice known as rapto, where a man kidnaps a girl and forces her to marry him, is still commonplace. Raping an underage girl is not against the law in many Mexican states if the rapist marries her. (244-5) [Cp. Deuteronomy 22:28-29]

On we jolted through the humped streets. A donkey with its ears cut off or perhaps frozen off in a bad winter was drinking from a filthy stream. Three drunk Tepehuans were passed out underneath a beer advertisement that read, "Always In Moderation." Periodically, Isidro would have to duck down in the passenger seat to avoid being seen by someone who wanted to kill him. Another truck pulled up alongside us with another shit-faced drunk at the wheel. "Isidro!" he yelled. We are sons of the grand raped mother! We are sons of obscene perpetrations! Come drink with me! You, gringo, you drink with me too." And these offers had to be declined with the greatest politeness and delicacy because as Professor Licon puts it, "To refuse a drink of liquor from someone that has cost all their salary or savings to impress their friends is almost a declaration of war, a very serious discourtesy and many times an insult that ends in tragedy . . . wounded masculine dignity is the most important motivation to explain the great number of killings in the Sierra."

"In a world of chingónes . . ." wrote Octavia Paz, "ruled by violence and suspicion—a world in which no one opens out or surrenders himself—ideas and accomplishments count for little. The only thing of value is manliness, personal strength, a capacity for imposing oneself on others." (245-6)

I was the only visitor that afternoon. The nearby village was deep in siesta and the only sound was the hot dry wind in the trees. Carved in stone by the entrance was an inscription about Villa: "Warrior of my fatherland, fist of the people, colt of fire, cry of the darkening storm, roaring avalanche, may your memory burn and your name crackle . . . gallop for us in your shining phosphorescence raising your flag." (250)

I had never been to Durango before and it threw me into a state of postmodern confusion. It looked so much like the Old West. Was this because the landscape was so similar to parts of West Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado but without the telephone poles, power lines, and billboards? Or was it because so many Hollywood westerns had been filmed on location in Durango for that reason? Sam Peckinpah made The Wild Bunch and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid here. (253)

There is only one species of scorpion in Mexico that can kill an adult human with its sting and Durangueños are enormously proud of the fact that it lives only in their state. (264)

I drove out of the mountains and then north across the plains and deserts and I didn't stop driving for fifteen hours until I was in striking distance of the U.S. border. I was ready to write about celebrity bathroom fixtures for a living, designer footwear, what your window treatments say about you. Some other fool could go into Sinaloa. I never wanted to set foot in the Sierra Madre again. The mean drunken hillbillies who lived up there could all feud themselves into extinction and burn in hell. I was out of courage, out of patience, out of compassion. They were sons of their whoring mothers, who had been fornicating with dogs. [END] (277)

|