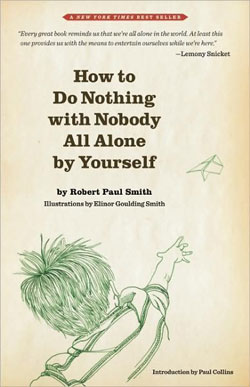

How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself

Robert Paul Smith (1958; rpt. 2010)

I find kidlore endlessly fascinating (maybe you remember, e.g., the Clothes Pin Match Gun page). I don't know whether kidlore persists as strongly as it once did. Maybe kidlore has been replaced by memes, or will be, and that'll be a shame, because memes are as temporary as anything can be, whereas kidlore went on and on and on.

Anything by Robert Paul Smith is worth reading, but my favorite book of his is How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself It was Smith's belief that in the 1950s, American kids had become somewhat wussified and unschooled in how to entertain themselves.

Imagine what Smith would think of us now. When I was a kid, every kid carried (or was presumed to be carrying) a pocketknife. There were no searches, metal detectors, or freakouts—and, oddly enough, an alarmingly low number of stabbings (I only ever saw two knife incidents that could be classed as accidental). As kids, we were told "The police officer is your friend," and we didn't believe it even then, when cops were slightly nicer, and somewhat less automatically brutal.

Nowadays, however, unfortunate kids forced into government schools get in trouble for, oh, say, biting a breakfast pastry into the approximate shape of a gun. And today's government school teachers and administrators often don't merely send kids to the principle: instead, uniformed and armed police officers come and book children—children—into jail. I'm not joking: kids these days are arrested and toted from one jail (school) to another jail (jail) for such horrific crimes as spraying themselves with perfume, throwing paper airplanes, or even just belching ("on a scale of 1 to 10 according to a risk assessment given by the jail staff, 10 being extremely dangerous," the burping child "scored a - 2").

All of that to say: kids, have a blast with this stuff, and let no one stop you!

If things were as they should be, another kid would be telling you how to do the these things, or you'd be telling another kid. But since I'm the only kid left around who knows how to do these things - I'm forty-two years old, but about these things I'm still a kid - I guess it's up to me.

These are things you can do by yourself. There are no kits to build these things. There are no classes to learn these things, no teachers to teach them, you don't need any help from your mother or your father or anybody. The rule about this book is there's no hollering for help. If you follow the instructions, these things will work, if you don't, they won't. Once you have built them my way, you may find a better way to build them, but first time, do them the way it says.

First thing is a spool tank. For this you need an empty spool. Here's one place your mother can be ootzed into the deal. You can ask her for a spool. If she hasn't got an empty one, you'll have to wait until she does. In the meantime, build something else. (9-10)

Now go outside and find a very smooth stone, like a sidewalk, and rub, gently, until the washer is nice and flat on both sides. You don't really need a stone, you can do it on a wooden floor, if your mother is someplace else. (11)

The other night, a friend of mine, who lived only six blocks away when we were kids, told me that he used to make the washers out of the paraffin that used to be on the top of jars of homemade jam. Now he tells me! (11n)

Another thing we used to do was make what we called a button buzz saw. This is something you can make in about five minutes any time you've got nothing special to do. (14)

[I]f you can't find a button or a spool at home, take a walk and go to the tailor shop, or cleaning store, or whatever they call it in your town or neighborhood. As I said this book is things you do yourself; so don't ask your mother to do this. (16-17)

While we're at handkerchiefs, we used to make blackjacks out of them. Not real blackjacks, not heavy or hard enough to injure anybody, but they were pretty good for fighting. You could catch a kid a pretty good shot with one, and he could thump you pretty good, but they didn't do any real harm. (20)

There were a couple of fairly idiotic things we used to do when we were just sitting around in the grass, which you might find fun. (22)

You may have noticed by now that the things in this book don't come in any sort of order; that some of the things I've told you about are for indoors, some for outdoors, some for spring and some for fall and some for winter: as I told you before, you're not supposed to do all the things in this book in order: when you've got the spool, build the spool tank. When you've got the burrs, make a burr basket. I think the best way to use this book is just to read it through once, and then put it somewhere where you can find it when you want it. And then one day, when you've got nothing special to do, hunt out an old handkerchief and make the parachute. Or find a button and make the buzz saw. But read the book through once. At the back, I'll put an index so that you can find out what you want when you want it.

One thing you're sure to have any old time is a pencil; and here are two things we always did with pencils, as soon as we owned a pocketknife. Right now, before I tell you about the pencils, let's have a little straight talk about a knife. I don't know how old you have to be before you get a pocketknife; that's up to your father. If you ask your mother, it'll probably turn out that she thinks you ought to be twenty-one before you can have one. I think you'll be able to work out something reasonable with your father. (26)

Now, here's something else that you're just going to have to argue out with your mother; I did with my mother, my kids did with their mother. A sharp knife is safer than a dull knife. A sharp knife cuts more easily, you don't have to use as much force on it, and you can control it. Nobody can do good work with a dull knife—and ask any carpenter, nobody can do safe work with any dull tool.

Now, it's got to be a good knife to be sharp. Nobody can put a good edge on a poor knife. A good one will cost more than a cheap one, but it's worth it. It'll take a good edge, it will hold it, and it will last practically forever. When I was a kid, we all thught the only good knife was a Case knife. They still make them, they're still good knives; there are lots of other good knives, but I know about Case. (27)

The only reason I'm even mentioning it is that people I've talked to claimed they knew a kid when they were kids who was able to make willow whistles. Maybe I'm just a dope about willow whistles and you'll be very good at making them. But everything else in the book I've made. I made them when I was a kid, and I made them again as a grownup, and they work. This is a guarantee. (31)

If you don't know what a willow tree looks like, go to the Public Library and get out a book about trees. You'll notice that all through this book, I advise you to go to the library when you want to find out something. I think just plain going to the library and getting out a book is a swell thing to do. It's something to do, when you've got nothing to do, all by yourself. It's a thing I still do when I've got nothing special to do. I just wander around until I find a book that looks interesting; let's say, a book about shipbuilding, or rockets, or a story by some author I've never heard of before. Now, chances are I'll never build a ship, or ride in a rocket, and maybe I won't like the way the author I never heard of writes. But it's interesting to know how someone else builds a ship, or plans to fly in a rocket, or how the author feels about things. (31-32)

Here's another place where the people I've been talking to don't agree. Some of them say sure, they remember this one, others say they don't. I think sometimes we did and sometimes we didn't. You see, in the days when I was a kid, you learned mumbly-peg from another kid, and the rules you learned were his rules. If he came from another part of the country, he taught you the way the kids played there: nobody, so far as I know, ever tried to write down the way to play mumbly-peg until I got stuck with the job. And believe me, the last thing in the world I want to see is an official rule book of mumbly-peg, or mumbly-peg leagues or championships. You can leave this one in, or take it out. It's your game, and you play it the way you think is right. Just be sure that when you play it with another kid, you're both playing the same game. (37)

The reason there'll still be arguments even with the rule is that sometimes it looks as if the guy is ootzing the knife up with his two fingers. It mostly looks that way when it's the other guy, rarely when it's yourself. Anyhow, this argument, like all arguments with your equals, is something you'll learn to straighten out by yourselves. (42)

Those people are around again, telling me how they played mumbly-peg. Okay, they called Wind the Clock "Slice the Cheese," and I told them that on my block Slice the Cheese was something entirely different, and it had nothing to do with slicing, cheese, or mumbly-peg. I feel sure your father will show you Slice the Cheese, or maybe he calls it Slice the Ham, but I don't know how happy you'll be to learn it. (52)

In any case, you hit the peg into the ground, and the loser had to pull it out with his teeth. Of course, if you got the peg far enough into the ground, the loser had to eat a little dirt to get at the peg, and chances are when he got his mouth full of dirt, he mumbled something—just what, I would not care to say. So, he mumbled the peg, and the game was called mumbly-peg.

But as I say, we never did that. I'm sure we would have, if we'd known it was a way to make somebody eat some dirt. You can do that part of it or not, as you please. It all depends on how you feel about getting a mouth full of dirt. (52-3)

It has been brought to my attention that some kids don't know how to make paste any more, that they think paste is only something that you can buy. With us, it was the other way around. We knew how to make it, and later on found out it was possible to buy it. Well, I'm not going to draw any pictures or give any careful instructions here. You take flour and water and mix it until it's paste, and if you have some salt you can put it in, too. I don't know if the salt does any good, but we figured we had nothing to lose. It wasn't our salt. (54n)

So I guess right here, there better be another little speech about danger, like the one about knives. It's my belief that things themselves are not dangerous. It's the people who use them. One man driving a car is safe as houses; another is a menace to everybody on the road. I thnk the man who is safe is safe because he knows how to drive a car properly, and the man who is a menace is a danger because he hasn't ever really learned to drive. Sometimes the dangerous man is dangerous because he just doesn' t care, which is even worse. You know kids like that, I'm sure.

But it doesn't seem to me the answer to safe driving is to do away with automobiles, nor does it seem to me any more sensible to do away with bee-bee guns because some kid you know is a dope.

I can't give you any better argument than that to use with your parents about any of the few things in this book that are dangerous; and I must say that as far as I am concerned, with my own kids, I show them how to use the dangerous things, then watch them do it for themselves, and if I see they don't do it just exactly the safe way, they don't get to use the dangerous thing until they prove to me that they know how to be careful.

It's got nothing to do with age, by the way; I know kids of seven that I'd trust with a knife, and I know men of fifty that I wouldn't trust with a sharp lollypop stick. (56-7)

I think you'll be pleased to find that this dart, used indoors, will stick to practically anything, curtains, furniture, sometimes even walls, and it does not leave a mark. I wouldn't suggest aiming it at the very best antique table in the livingroom, because even a little mark would convince your mother that the dart was dangerous.

Of course it is, and I'm here to tell you if I ever saw a kid throw one of these at another kid, there'd be a ruction in the house that wouldn't die down for a long time. (58)

If you want them [horse chestnuts] to shine more, take them and rub them up against the side of your nose. Perhaps you've seen your father or someone do that with a pipe. There's oil on everybody's skin there and it oils up the chestnut or the pipe and makes it shine. (65-6)

I'm not sure that we called these next things bull-roarers when we made them as kids, but I've since found out that's what they're called. I've also found out that they make them in many parts of the world, and in some primitive tribes, they're used by the grownups to scare devils away. We just used them to make enough noise to drive grownups away. (73)

You have now learned, even if you don't know it yet, something about the science of physics. I won't tell you what it is, but later on, when you study science, or right now, if you are studying science, you'll find out. The reason I won't tell you is because if I don't, maybe you'll go to your library again and get out a book about elementary physics, and that'll be one other nothing you can do with nobody. (75)

There was a kind of shopping we used to do when we were kids, which was just walking down our block and seeing what people had thrown away in the trash can, and taking out those things that looked useful. (80)

But if, after all this, you do happen to run across a busted umbrella, the first thing to do is to get all that remains of the cloth off the ribs, and then pry the ribs loose from the center part. You can use brute strength, pliers, or intelligence. The thing is to get them loose. (81)

I made a lot of them, and took them to school with me, and I guess my teacher liked to shoot miniature slingshots, too, because she made a collection of mine. (84)

I don't know how old you are, and I really don't know any more how old I was when I did the different things in this book, so if you find that some of the things are too old for you—wait until you're old enough to do them. If you find that some of the things in the book are too young for you, first figure out if they're really too young, if nobody else knows that you're doing them. I know that when I was a grown man, my wife and I went to live in Mexico for a while, and walking down the street one day, I saw a whole bunch of kids playing with what was, for me, a brand new toy. It was a yo-yo, and I'd never seen one before. I bought one—I told the shopkeeper that it was for my kid, but I didn't have a kid then, and I brought it home with me. Now certainly a yo-yo, as a matter of fact any toy, was too young for a man almost thirty years old, so I used to sneak out in the back yard when I wanted to learn how to use a yo-yo, and any time anybody came to the house when I was doing it, I stuck it in my pocket and pretended that I had been out back doing something important and grownup.

So, first of all, remember that the name of this book is How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself and if some of the things sound a little childish, figure it out: do you think they're too childish, or do you think that if someone else saw you doing it, he would think it was childish? And if you really are too old to do some of these things, why don't you show your kid brother how to do them, or your little sister, or any little kid on the block? He or she will think they're great things, and they'll think you're great for showing them. (90-1)

Silly? You bet. But sometimes it's fun to be silly, and didn't you laugh just the other night when the man on television put on a funny hat? (93)

If you'll pluck the string, holding the whole thing by the yardstick in your closed hand, bending the yardstick into more or less of a bow, you'll produce a kind of ba-voom noise, which sounds very much like some of the noises you've heard on television when the man with the checkered suit has had one drink too many. (99)

I don't know what the name of this is. It's just a ba-voom thing. (100)

Teachers used to take these away from us, too. (109)

There's a way of making a helicopter, too. By the way, when I was a kid, it was clearly understood that there never would ever be a real full-size, man-carrying helicopter. It had been very carefully proven, scientifically, that it was impossible ever to make one that would get off the ground. (114-15)

I'm not making fun of scientists; it wasn't so long ago that all the scientific theories in the world were based on the theory that it was impossible to split the atom. Well, of course. Everything is impossible until it's done. Then whatever has been done is possible, and there's a new thing that's impossible. (115)

That stuff called Silly Putty works, too, but that costs money. (119)

Of course, you never know how long it's going to take for the match to come loose. I'll guarantee only one thing; it won't ever let loose at the exact moment you're expecting it. If you put it on the table next to your father when he's making out his income-tax return, it should produce some interesting results. He may tell you what he did to scare his father when he was a kid, and he may even show you what his father did to him when he scared him when he was a kid. (120)

There are lots of other things you can do, all alone, by yourself, but these are about all I can think of right now that aren't specialized in some way.

I'm really serious about the library; that's the best place to learn more. We did lots of other things when we were kids, like collecting bugs, and wild flowers, and frogs, and snakes, and stones—and in the library I promise you there will be a really expert book on each of these, and on many other subjects, written by people who've made a life study of those special things. There will be books about trees and radio sets and telescopes and badminton and Indian crafts and metal work, about how to make bows and arrows, how to swim, how to—oh, there's no end. There's even a book on how to find a how-to book.

Some silly grownup has even written a book on how to read a book.

But if you've gotten this far, I know you know how to read a book.

There's only one thing left to tell you: the name of this book is How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself. I understand some people get worried about kids who spend a lot of time alone, by themselves. I do a little worrying about that, but I worry about something else even more; about kids who don't know how to spend any time all alone, by themselves. It's something you're going to be doing a whole lot of, no matter what, for the rest of your lives. And I think it's a good thing to do; you get to know yourself, and I think that's the most important thing in the whole world. (120-1)

|