Moon Shot Memories: The Apollo 11 Landing from a 7-year-old's Perspective

My grandparents were older than the invention of the airplane. My parents were older than plastic. Ordinarily I might say I'm older than the Internet, but it's July of 2019, so instead I'll say I'm older than the first lunar landing. Old enough, even, to remember it.

One might expect that people who had lived through decades filled with technological leaps would have been at least somewhat enamored of science. Airplanes and plastic notwithstanding, however, ours was not at all a science-y family. That we were Baptists forms probably at least part of an explanation. My father did regard himself as a lifelong flight enthusiast, which in a sense he was, except at the end of the only flight on which we were ever passengers together, he looked out the window after the airliner touched down and elbowed me to draw my attention to the engine, which he believed was "falling apart!" What he saw was merely the normal operation of the clamshell thrust reducer mechanism on one of the 737-200's engines. I would later come to realize that his interest in "flight" actually extended only as far as aircraft capable of dropping bombs on people or firing guns at them. But he did seem to enjoy displaying exaggerated exasperation every time his explanation of how airfoils work, an explanation that always included the same simple diagram, was once again utterly lost on Ma. I never could guess what Ma might or might not know. She once asked me in all seriousness whether it's possible for clouds ever to be behind the Moon instead of in front of it. You'd assume that to be a fundamental piece of knowledge, but then, we were fundamentalists.

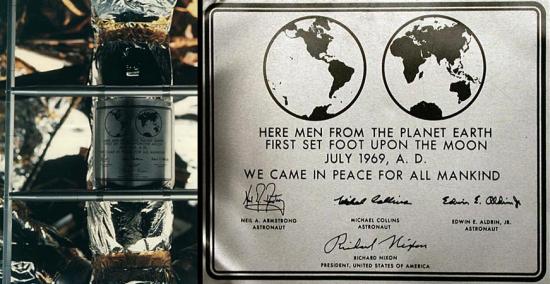

For my parents to pay special attention to an event it had to be something they considered to be (as my father would announce importantly to us) "His-TOR-ical!" That nearly always meant an event with some patriotic element to it, such as the evening my father frantically grabbed his Instamatic to snap photos of our old television console (later being baffled by the horizontal lines on the TV screen in the snapshots) as the presidency of the U.S. was surrendered on live TV by a man whose name and signature were inscribed on a plaque affixed to a manned space ship that only a few years before had landed on the moon.

Today most of us seem to have forgotten that both before and after Apollo 11 the majority of Americans did not support the Apollo project and considered it a poor use of money, a judgment reflected in the assessments of Tom Lehrer ("20 billion dollars of your money to put some clown on the moon"), Gil Scott-Heron (“Was all that money I made last year / For Whitey on the moon?”), and Larry Norman ("They brought back a big bag of rocks / Must be nice rocks").

In July of 1969, though, almost everybody's attention was gripped by Apollo 11. As an almost-8-year-old, I was allllll the way into it. The day of the moon landing my family, along with the rest of the world, was following along with the adventure as it unfolded. We gathered excitedly around the TV with assorted relatives at my grandparents' house, a tidy old two-story in which Ma had grown up in Portland, Oregon and where every summer we would travel from our home in

Arizona. A few months before our 1969 trip we had moved from my birthplace in a forest down to a tiny town in the low desert, a place most people avoided staying even one night (it had only two motels, both mostly empty most of the time, one of which was our home address at the time). Ma disliked our new town even more than she had the previous one and my father missed the hunting and fishing opportunities in the mountains, but for me the desert was almost a salvation, a place of new independence, where I got my first bicycle and had the run of the place, when I could get away with it, which gave me more time away from a family situation that had up to then been almost completely unavoidable. Our trips to Portland represented to me a similar liberation and for the same reason because my father was able to stay away from his job for only two or three weeks, whereas the rest of us would stay four or five. Those precious weeks after he left were a vacation indeed.

Arizona. A few months before our 1969 trip we had moved from my birthplace in a forest down to a tiny town in the low desert, a place most people avoided staying even one night (it had only two motels, both mostly empty most of the time, one of which was our home address at the time). Ma disliked our new town even more than she had the previous one and my father missed the hunting and fishing opportunities in the mountains, but for me the desert was almost a salvation, a place of new independence, where I got my first bicycle and had the run of the place, when I could get away with it, which gave me more time away from a family situation that had up to then been almost completely unavoidable. Our trips to Portland represented to me a similar liberation and for the same reason because my father was able to stay away from his job for only two or three weeks, whereas the rest of us would stay four or five. Those precious weeks after he left were a vacation indeed.

I recall no specific thing any of my relatives in the room might have said to mark such a stupendously momentous occasion. Gramps kept his own counsel regarding the moon, space travel, and most everything else, always, as far as I ever noticed. Ma told me she worked one summer as a teenager at his dental practice and was shocked to discover that he chattered all day long, a smile and a joke for every patient. By the end of the day, to Granny's dismay, Gramps was pretty much talked out. My cousin and I were obsessed with baseball back then, often swapping baseball cards on the living room carpet as Gramps read his newspaper, yet not until after his death several decades later did I found out that he had been an ardent baseball fan.

I'm sure family members must have given forth with general expressions of wonder—"Mercy sakes!" and "Land o' Goshen!" and the like—but I doubt we could have generated much more than the sort of unfounded speculations and uninformed guesses that fill the 24-hour news stations today. Certainly there was nothing happening in the room to draw the attention of kids away from the TV screen on which nothing of interest appeared to have happened since the lunar module had touched down. Just as I used to excitedly burst out of the car the moment we arrived in Portland after a three-day car journey cooped up with the family, I had expected the astronauts would hop out onto the moon as soon as their space craft touched down on the surface of it.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration, not run by impatient children, had instead scheduled the astronauts for post-landing equipment checks to be followed by a sleeping period. Wasn't that just like grown-ups, always wanting to put you down for a nap just when an afternoon was getting interesting. Can you imagine trying to sleep after the adrenaline-filled experience of landing on the moon under manual control with only 15 seconds of fuel to spare? I used to hate being ordered to take a nap when I was so hopped up I couldn't possibly have fallen asleep, and that was without having just landed on surface of the moon!

As it turned out, Armstrong and Aldrin didn't nap. Their alotted rest time ended up being filled by checks and tests to ensure their craft would be able to successfully get them off the moon, which makes all the sense in the world and the moon to boot, but to a 7-year-old's laughably limited attention span and near-total lack of patience, the idea of not instantly leaving the spacecraft was not just incomprehensible, it was intolerable. After probably not even an hour of waiting around for Armstrong and Aldrin to get the go-ahead to exit the spacecraft and bound around on the moon, my cousins and I could no longer endure. Among adults Walter Cronkite was known as "America's Most Trusted Newsman," but to us kids he was just some old guy blabbing over a bunch of diagrams and animations.

The grownups scolded us when we got up to go outside and play in the yard, but we called over our shoulders for them to let us know when something important happened—as if something important weren't unfolding moment-by-moment! Such is the concentration of youth.

It wasn't that we had lost interest or didn't care. I can recall during childhood walking away from televised basketball and football championship games to go outside by myself and shoot baskets or toss the football onto our pitched roof and make heroic, Super Bowl-saving catches. Youngsters are often drawn to enact for themselves whatever has caught their imagination at the moment, maybe partly to feel, at least in some small way, participants in the world of adults from which they are mostly excluded.

At that moment our immediate world of adults was so wrapped up in the Apollo coverage that no one thought to order us back into the house even when it was hours past the time parents typically required young children to come indoors for the night, even in those days. We just kept on throwing frisbees and taking turns riding up and down the sidewalk on a tricycle or on an old metal toy tractor that Granny kept around for us.

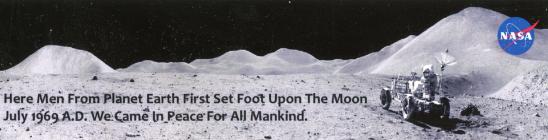

I'll bet NASA would have loved it if they could have put the astronauts on the moon on Independence Day—the 4th, rather than the 20th—but right then I could hardly have felt any more free. I lay on my back on my grandparents' small lawn, more of a mound than a yard, and looked up at the moon hanging there in the sky, thinking about how there were men up there, and wondering why our parents hadn't been able to see the landing site through their modestly priced pair of binoculars, and pondering that the astronauts were people more or less like us, who ate the same breakfast cereals we all ate, probably watched the same dumb TV shows the rest of us watched, and yet there they were, almost a quarter of a million miles away from us, on the surface of the moon, themselves the focus of most TV watchers in the world that night.

To be on the moon struck me as the ultimate freedom. I had often wished I could leave our household to go live elsewhere, forever. The idea of that elsewhere being some other world suddenly no longer seemed outlandish. I began to believe that by the time I was the age my parents then were, people might be able to start living on the moon. After all, within the lifetime of my grandparents planes had come into existence and it wasn't many years later that there were commercial flights. Now, in my lifetime, there existed rocket ships! That I could one day fly away and not have to return began to feel inevitable.

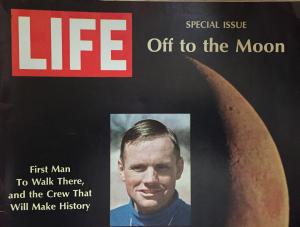

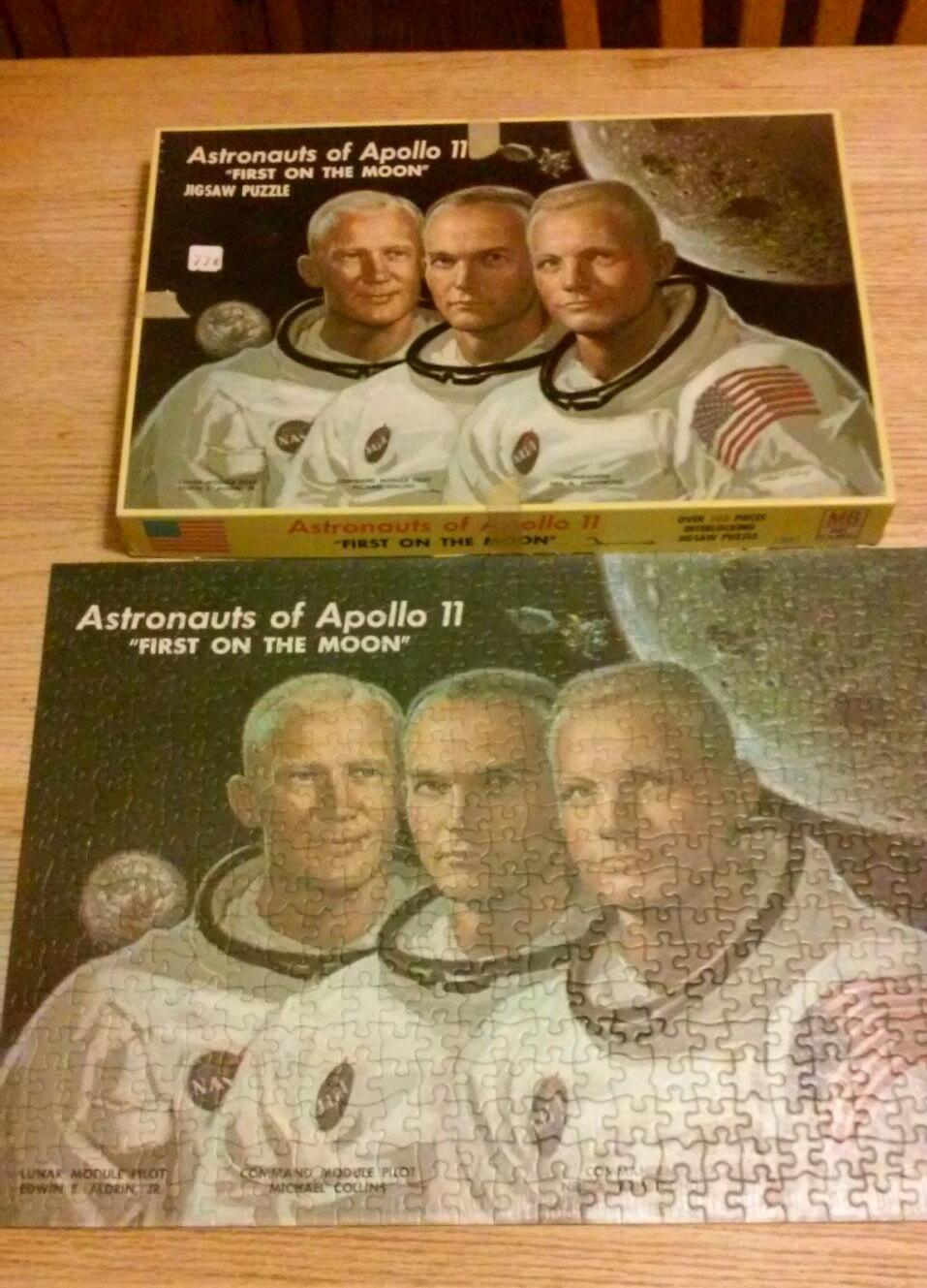

In the coming months I would tape Apollo 11 posters to my bedroom walls (they're rolled up only a few feet from me as I write this). I'd assemble and reassemble, a dozen times or more, a 500-piece jigsaw puzzle picturing the three astronauts. For several years I would collect any roadside mechanical junk I found and hide it in the back yard under a tarp behind an old unused doghouse, convinced that a rocket ship cobbled together by a grade-schooler—even one who had acquired only the bare minimum of mechanical know-how, thanks to avoiding as much father-son garage time as possible—could make it to the moon.

It was nearing 8 o'clock, though still light outside, when we finally got the call (or, rather, the yell, the old man being as loud as Gramps was quiet): "You kids GET IN here, RIGHT NOW!" he shouted from Granny's front porch. "They're about to leave the ship! This is hisTORical!"

A nurse with experience treating astronauts later observed that they "have something, a sort of wild look ... as if they regret having come back ... a rage at having to come back." I think even as a 7-year-old I could have understood that feeling. And I understood all too well that for the time being I was stuck where I was. But Apollo 11 enticed me with a promise: maybe not for long.

© Deuce of Clubs

|