![]()

![]()

|

|

|

|

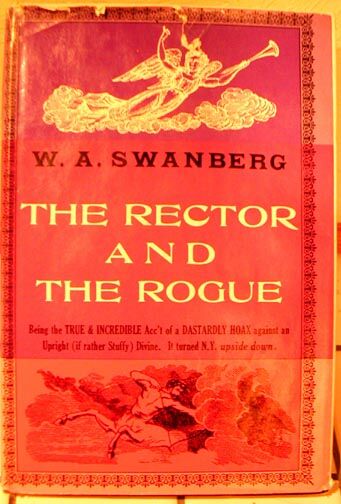

The Rector and the Rogue (1968)by W. A. Swanberg |

|

W. A. Swanberg wrote the book on Fisk, Sickles, Hearst, and Pulitzer, but The Rector and the Rogue was his best work. New York's in a panic these days, but this is the story of one hoaxster who put 1880 Manhattan in a tamer tizzy.

This book represents a sincere effort to right a historical wrong—to restore belatedly to a great and neglected American at least a fragment of the recognition he deserves. I refer to E. Fairfax Williamson of Pittsburgh, New York, London and many other places, some of which he preferred not to mention. (153) This work also examines the astonishing collision (particularly at two points in history) of a moral issue and an artistic concept. It raises the question of how far the originator of an ingenious hoax is justified in imposing on a relatively few honest and long-suffering victims in order to entertain millions of people with a rich and satisfying performance that would be impossible without such imposition. Or, to reverse the proposition, should these few victims really complain when it can be shown that without their unwilling and disgruntled participation, the multitude and indeed the world would be deprived of a masterpiece? The very tone of the question betrays an unscientific bias for which I make no apology. (153-4) "It is surprising," he [The Reverend Doctor Morgan Dix] said, "that the very conveniences of civilization can be made the source of so much vexation and annoyance." (15) Dr. Rylance was less concerned than he might have been because his only brother was not named Will, had never been in Berlin and had a hand totally unlike this. He noted that the handwriting was the same as that on the "Mrs. Dr. Dix" postcard, and kept both missives as souvenirs of human eccentricity. (42) "As you don't know me, and as I never was within the doors of your saloon, it looks very much as though you were trying to black-mail me." (47) "Your honor, a man who lives on the corner 3d Avenue and 9th St. New York named D. Buckley might tell you something about the murder of the woman, he talked pretty free of it while he was drinkin last night. — A honest Mechannick who don't want to be known" (48) Some of the evidence actually seemed to suggest that the hoaxer's motive was amusement rather than profit, although cynical policemen could not be expected to give credence to such a romantic theory. Nevertheless, despite the mischief Joe had caused, they could scarcely repress some admiration for the broad sweep of imagination displayed by the culprit who, working with the humblest of weapons, penny postcards, succeeded in throwing confusion into the nation's manufacturers, confounding the used-clothing dealers of the Lower East Side, and embracing in his intricate design subjects as seemingly remote as the Irish famine, epileptic fits, a murder in Paterson and the bishops of York and Execter, to name only a few. (50-1) To hard-bitten newspapermen, dignity was always a questionable posture. Anyone who could puncture it, as in the case of Dr. Dix, the mayor of Paterson and a few others, merited approval. One who could deflate it with the added ingredients of amusement and mystery was nothing less than a public benefactor. The Dix affair contained the timeless element of comedy—the surprise assault of the mundane and ridiculous on pride and aristocracy. (59) [Chapter title:] SUBTLETIES OF JOKESMANSHIP (60) Practical jokes of such depth and complexity had to be judged on a basis of points won or lost in the many levels of their planning and performance. Joe surely deserved points because he had maneuvered his forces so that no damage had been done except to complacency and order. (63)

Under headlines such as "Terrible Scenes of Mutilation" and "A Shocking Sabbath Carnival of Death". . . . (65) "It seldom happens that so much pleasure is given so cheaply." (72) There he had met another guest, E. Fairfax Williamson, whom he had known very slightly in New York. Williamson, always the very glass of fashion, surprised Peters by the warmth of his greeting, shaking his hand and expressing pleasure as if they were very old and dear friends. (89-90) He repeated this argument in several different ways to make certain that Gayler understood the logic of it and would rid himself of the horrid suspicion that there had been so much as a thought of money. Never! The little man was deferent, in fact positively charming, but he was very firm on this point. He was either anxious, or anxious to create the impression that he was anxious, to cooperate in unraveling the puzzle which he personally constituted but which (he said) he could not personally solve. "I seem to have eccentricities at times," he said, "which are too much for me to understand." (98) Gayler questioned Williamson further about his motive when they reached the Baltimore police headquarters. The little man knit his brows and pondered. "I suppose it may have been a practical joke," he said in the manner of a man in utter ignorance who is making a wild guess. (100) The reason he gave for his two stays at the Windsor Hotel was simply that he liked to get around. . . . (101) Gayler, as he described it afterward, felt that Williamson had the kind of magnetism found in such platform orators as Robert Ingersoll or James Blaine—an ability to kindle actual affection on the part of listeners as well as to command their interest. One had to be careful while in his company or one would begin to like him. (101) [The prankster's dilemma:] He seemed in the predicament of being quite proud of his exploits, anxious on the one hand to get proper credit for them and fearful on the other hand of suffering punishment for the illegality that accompanied the credit. (111) [Theodore] Hook himself wrote in annoyance, "Copy the joke and it ceases to be one—any fool can imitate an example once set." (113) It seemed evident that good jokesmanship usually was accompanied by moral failings of one kind or another which one accepted good-naturedly as one did the soprano with the divine voice and shrewish temper. (114) Perhaps their [Hook's and Williamson's] greatest resemblance (outside of their turn for humor) lay in their passion to be in the public eye. Neither was happy unless he was creating a sensation. On one occasion, when Hook was touring Wales by carriage with his friend the actor Charles Mathews, Hook suddenly complained, "The scenery is all very fine, but nobody looks at us; the thing is getting a little dull." He bought a box of large black wafers, carefully affixed them to their white steed in the geometrically regular design applied to rockinghorses and thereafter drew the attention of all Welshmen. (115) As a true Fairfax, however, he rushed home at the outbreak of the Civil War. Fragments of information that now poured in as a result of his arrest pictured him as a poseur of marvelous persistence who had flitted about the world ever since, leaving a murky trail of doubt, misunderstanding and disagreement. (118) This instance of his being accused by both sides was typical of his capacity for fooling everyone and spreading utter confusion—a field in which even Hook partisans had to admit that Williamson was far superior. (118) Reporters kept urging him to disclose the rest of his career—in effect, to furnish his autobiography. He declined, probably fearing heavier punishment. Indeed he would have said nothing about the Hyeres, Geneva and London performances had they not become known through other channels. Thus he was in the position of a newly discovered painter who has created several known and charming canvases and who insists on keeping dozens of others locked in his garret, unseen. (134) He would not disclose the source of his wealth. The answer given by this man who had had virtually no known honest income for years was in his best vein of the absurd: "I did save my money at times for a bit of a fete." (142) All along the investigators had missed the point in their estimate of his motive in writing the cards involving Dr. Dix. They had looked hard for a grudge against the rector. Unable to find one, they had fallen back on the extortion theory. In one sense the error was a mere technicality, for it probably made no difference in Williamson's ultimate fate. But it was of first importance in its illustration of the quagmire of misunderstanding the law could sink into when confronted by the esoteric. Blackstone and the muses could not communicate. They spoke different languages. (146) "The New York authorities could not seem to realize that for him an artistic motive was enough. Even yet they did not grasp the fact they they and their whole city had been manipulated in a vast achievement of dramaturgy—this whole enterprise of [his] was the result of a theatrical concept never before approached in ambition, scope and daring. He had appointed himself writer, producer, director and stage manager for a drama encompassing the metropolis, using its streets, churches and buildings as his stage, its newspapers as his publicity organs, and a huge complement of citizens, manufacturers, business and professional men, the police and public officials as his players. As casting director he had picked the famous, dignified, severe and sensation-hating Dr. Dix to be a victim simply because he would be perfect in the role, the man best endowed to react entertainingly and with maximum publicity. Various scenes in his extravaganza were laid in Twenty-fifth Street, Trinity Church, Trinity Chapel, Buckley's saloon, the newspaper offices and other places. And as producer, [he] had proudly entered—this time as a spectator, a part of the audience—the real-life theater he alone and unaided had devised. He had paraded Twenty-fifth Street to watch the comedy which he had framed for the living world and whose critics gave him front-page space in every newspaper in town. It made him feel like a god—and why not?—to see and read of thousands of people in his cast enacting, all unknowing, the roles he had created for them, with literally millions watching in the newspapers a drama so suspenseful that it continued for weeks." (146-7) When Williamson went to court on April twenty-sixth, the indictment read in part, "that heretofore, to wit, on the fifteenth day of February in the year of our Lord, 1880, in the city of New York, in the county of New York aforesaid, Eugene E. F. Williamson, otherwise called `Gentleman Joe,' connived as much as in him to lay to vex and annoy one Morgan Dix and with intent thereby to extort moneys from him. . . ." The plea was guilty. (148) Perhaps the cruelest of blows to strike him was public neglect, the inevitable fate of the great. No one but his lawyer came forward to speak for him. The millions in his newspaper audience, once so enthusiastic, had dropped him simply because the play was finished and house shuttered. Even his hard-core admirers, those who understood him so well, were subject to human fickleness and had fallen away after weeks had passed. He seemed not to have a friend in the world. (149) When Hook died, a quartet of his cronies who had participated whole-heartedly in a wake held for him proposed that he be memorialized in Westminster Abbey. But of course nothing was done about it and he has since become as forgotten as Theophilus Cibber. When Williamson died, not even that drunken honor was done him. Sic transit gloria mundi. He did not even leave a small coterie of disciples to ponder an interesting question: since he left this world at forty, in the full flower of his talents, was it not possible that had he lived on he might have exceeded the artistry of his Dix-Buckley effort not once but several times? (152) |

|

|

|

|