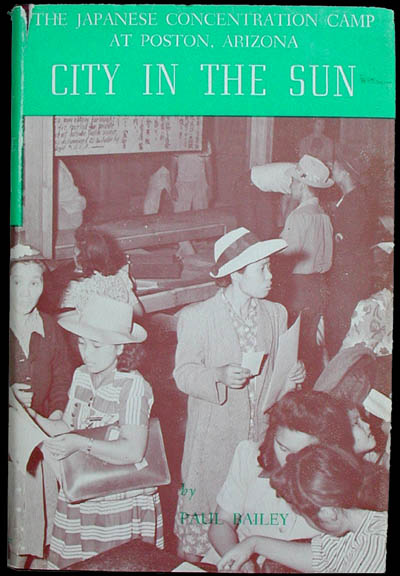

City in the Sun: The Japanese Concentration Camp at Poston, Arizona

Paul Bailey (1971)

"'We must move the Japanese in this country into a concentration camp ... and do it damn quickly,' says Representative A. J. Elliott to the House. 'Don't let someone tell you there are good Japs .... '" (30)

The two days that followed were days of complete madness. Most of the Issei men, so essential in this grave crisis, were in jail, along with the more argumentative of the Nisei men. The entire burden of evacuation was thrown upon the shoulders of women, children, and those of the Nisei generation who had escaped the governmental dragnet. They had forty-eight hours to settle all their affairs, pack their belongings, sell businesses, boats and furniture, and leave the Island, their homes, and their town.

Harshly, and without mercy, the government had ordered them to move. Where they were to go, no one knew. No means of transportation had been provided by those who hurled the ban. No housing had been promised. Californians were in no mood to receive three thousand indigent and homeless Terminal Island Japanese—individually, or collectively.

"People were in panic. Businesses were sold at great sacrifice. In some cases, expensive equipment was destroyed by the owners who could not bear to part with them at the ridiculously low prices that were being offered. Junk men and non-Japanese neighbors swarmed to the Island, purchasing their furniture for practically nothing. Stealing was a frequent occurrence during these two days. The government did not provide trucks to move furniture, and many of the people did not have enough money to pay to have them moved, so they left them behind. The JACL was successful in obtaining fifteen trucks for the people's use, but this number was hardly adequate." (31)

"What really got me was the government [state] sales taxman who came around during the 48-hour rush, and who, with an expression of ease, sat down on the stool and started checking up our sales. Here we were working as if it was a matter of life and death, and he, without any respect for our precious minutes, came over and collected to the last penny." (32)

There was heroism everywhere—women and boys doing men's heavy work. There was a forced cheerfulness about it—the nihonjin way of hiding heartbreak. The nihonjin smile that masked the contemplation of suicide. (33)

Someone in Washington had pressed a button, said a word, and their homes and community were no more. (35)

By now the newspapers, especially in California, had shifted from pre-war criticism and hatred of its Asiatic populace, to shrill hysteria. They demanded immediate and complete removal. Navy and Army wives, returning mostly from the holocaust at Pearl Harbor, brought back to the States their tales of sabotage and "fifth column" activity. These rumors were later proved to be entirely false. But in these critical weeks, it took only these stories to intensify the fear that similar activities might take place along the vast shoreline of the West Coast. (38)

Since many Terminal Island men had not yet been released from jail, the automobiles, following the long line through the sentry-guarded race track's outer gates, were mostly driven by women, and were heavily-burdened with the personal possessions they had been able to save. Speedily, efficiently, the cars were unloaded, and every bag and parcel tagged. Then the cars were surrendered, a receipt issued, and they were driven out to the vast parking area, to be impounded for the "duration." Most internees never saw their automobiles again. (41)

Military guards herded the last stragglers aboard the throbbing busses. One by one the big vehicles peeled out—through the circular drive, out through the sentried gates, heading east on Highway 66 toward the great new camp in Arizona. (59)

The great camp, being built in three community units, had been named Poston—in remembrance of Charles Poston, revered pioneer, and "father of Arizona." It was located on tribal lands of the Mojave and Chemehuevi Indians, and therefore geographically at least, under the thumb of the Indian Bureau. But while it was near the Colorado River, it was not directly on it. Of the ten great camps abuilding, the WRA had located Poston in a wilderness of desert, in the flat basin east of the river, geographically midway between Blythe and Needles, and in one of the hottest and most arid spots in America. Charles Poston, just and farseeing pioneer, were he alive, would have probably disowned the barrack city of tarpaper and pine, rising in the desert where he had once chased Indians, and now was named in his honor. (63)

Blythe was full of soldiers. One couldn't help but observe them, because they eyed the evacuees warily, as though they already were looking upon the enemy. It was explained to the nervous travelers that the soldiers of Blythe, who hovered in questioning wonder about the giant caravan of Japanese, were being trained, under command of General George Patton, for desert warfare, under desert conditions. (64)

Accepting the complacent role of the vast majority of evacuees, they had cooperated willingly, even though surrender to incarceration meant financial ruin. All of them were full of resentment and protest, but there had been few evasions and hideouts. Where could there be concealment and refuge, when one wore the face of Nippon?

It was already ending in disaster for the few brave souls who dared test the constitutional right of the government to impound its citizens on a racist basis. Gordon Hirabayashi, a Nisei citizen of the Quaker faith, and a senior at the University of Washington, had intentionally and deliberately violated the Japanese curfew law, which militarily demanded that he, along with all his race, remain indoors between 8 p.m. and 6 a.m. He was arrested, and sentenced to three months imprisonment. He appealed the conviction, but his case was to drag itself all the way to the United States Supreme Court before, in 1943, the validity of the military order was unanimously sustained—and Mr. Hirabayashi no longer had a case.

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, a young American citizen, in love with a Caucasian girl, refused to leave his home in San Leandro, California. His intention was to submit to plastic surgery, marry his hakujin sweetheart, and hide out for the duration. But the FBI caught up with him. He was convicted in a federal district court for refusing to comply with Civilian Exclusion Order No. 34, and imprisoned. Korematsu, with legal help of the American Civil liberties Union, was already battling his way to the Supreme Court. But he too was destined to lose. It would be December 18, 1944, before the highest court in the land, in sustaining his conviction, would uphold the constitutionality of the Evacuation. This landmark decision still hangs like a sword over all minorities, and all Americans. (69-70)

Poston, they soon discovered, was located on Indian land, a sort of lost world between Wickenburg and Needles—and one of the hottest spots imaginable. Actually it was Indian reservation, housing twelve hundred Mojaves and Chemehuevis, and therefore technically under the thumb of the Honorable John Collier and his Bureau of Indian Affairs. Many internees, wise enough to understand, were alarmed with the thought that Japanese Americans were now slotted in with the Indians on a tribal reservation. Knowing the Indian Bureau's dismal record in handling the welfare of their aboriginal charges, they had reason to be doubly worried. (79)

In Washington some official minds must have been at work trying to unravel the complexities of evacuation, or at least to have some awareness of the physical and psychological shock which the internment camps had brought upon the evacuees—though as the Arizona summer burned itself out to fall, one could see no discernible evidence of any such compassion or understanding trickling down to the frame and tarpaper world of Poston. In the lower echelon of management, Mr. Wade Head, Mr. John Evans, and their assistants, were competent, hard-boiled administrators. But to them, apparently, a Jap was a Jap; with no particular shade of difference. (89)

The first big push at Poston was the War Relocation Work Corps. Every internee—resident, or new arrival—was expected to sign themselves into the grand concept of complacency, compliance, and busy hands. Most of them scribbled their names to the mimeographed document with the same ennui they signed everything else; many without even reading it. Only a few of the hard core and embittered aliens refused to accept this or any other pledge.

I swear loyalty to the United States and enlist in the War Relocation Work Corps for the duration of the war and fourteen days thereafter in order to contribute to the needs of the nation and in order to earn a livelihood for myself and my dependents. I will accept whatever pay the War Relocation Authority determines, and I will observe all the rules and regulations.

In doing this I understand that I shall not be entitled to any cash or allowance beyond the wages due me at the time of discharge from the Work Corps; that I may be transferred from one relocation center to another by the War Relocation Authority; that medical care will be provided, but that I cannot make a claim against the United States for any injury or disease acquired by me while in the Work Corps; that I shall be subject to special assessments for educational, medical and other community services as may be provided for in the support of any dependents who reside in a relocation center; that I shall be financially responsible for the full value of any government property that I use while in the Work Corps; and that the infraction of any regulations of the War Relocation Authority will render me liable to trial and suitable punishment. So help me God. (90)

Out of sheer boredom on Sundays there was heavy participation in the Christian services. (93)

Naturally there was uneasiness in the upper echelons of management about the Buddhist upsurge. Some of the Anglo-Christian bosses openly labeled it "paganism." (94)

But like the Christians, the Buddhists were hopelessly splintered as to sects and formality of worship—the Shin Shu, the Odaishi, and the Micheron, all quarreling for rights. (94)

There was, however, a feature about these aquatic diversions unique to Poston, The pools seemed to draw almost as many rattlesnakes from the desert terrain as they did swimmers from the internees. As a safety measure, the surrounding scrub brush was cleared away. But even then, daily, the sidewinders and the king-size Arizona diamondbacks had to be ladled from the pools in order to keep them even moderately safe for the enjoyment of the swimmers. (100)

The physical travail and mental suffering, always increasing rather than diminishing, kept Poston's makeshift hospital constantly full. The "Poston zephyrs," in which the savage, swirling desert winds laid their gritty filth into every shelf and corner of the tarpapered tenements were bad enough. But the coughings and the wheezings were indicative of the fact that emphysema, tuberculosis, and that dreaded form of desert silicosis, already endemic in the Army camps, were alarmingly present, and aggravated by the wind-blown dust. (108)

The internees at Poston and Gila camps were being caricatured by certain newspapers as "little brown enemies," pampered and fed by the government. While Arizona babies cried for milk they could not have, the indolent and healthy "Japs" were reported to never be in want for this or any other commodity.

Never was it mentioned that Poston internees were subsisting on a per capita food budget of thirty-seven and one-half cents day. (110)

The University of Arizona refused to cooperate in any plan to continue the college education of the evacuees, and its President gave as the reason, 'These people stabbed us in the back at Pearl Harbor.'" (110)

A poem, written by some unnamed Nisei, freely circulated, read at the fire circles, and posted on the block bulletin boards, mirrors the anguish:

THAT DAMNED FENCE

They've sunk the posts deep into the ground

They've strung out wires all the way around.

With machine gun nests just over there,

And sentries and soldiers everywhere.

We're trapped like rats in a wired cage,

To fret and fume with impotent rage;

Yonder whispers the lure of the night,

But that DAMNED FENCE assails our sight.

We seek the softness of the midnight air,

But that DAMNED FENCE in the floodlight glare

Awakens unrest in our nocturnal quest,

And mockingly laughs with vicious jest.

With nowhere to go and nothing to do,

We feel terrible, lonesome, and blue:

That DAMNED FENCE is driving us crazy,

Destroying our youth and making us lazy.

Imprisoned in here for a long, long time,

We know we're punished—though we've committed no crime,

Our thoughts are gloomy and enthusiasm damp,

To be locked up in a concentration camp.

Loyalty we know, and patriotism we feel,

To sacrifice our utmost was our ideal,

To fight for our country, and die, perhaps;

But we're here because we happen to be Japs.

We all love life, and our country best,

Our misfortune to be here in the west,

To keep us penned behind that DAMNED FENCE,

Is someone's notion of NATIONAL DEFENCE!

(113-14)

The Hawaiian boys, in quaint perspective, called themselves buddhaheads—but they were good soldiers—gay, carefree, and tough. They, in turn, labeled the Japanese service men from the mainland as kotonks. The kotonks—embittered by the roust of their parents—were not nearly so gay and carefree. But all of these soldiers—to a man—resented being called "Japs." (143)

It was there they also had participated in one of the war's most peculiar battle experiments. As part of the D-Series Maneuvers, a detachment was sent to Cat Island, near Gulfport. The government, or some Army brasshead, had spawned the idea that Japanese people carried their own peculiar body stench—maladorously different from that of one hundred percent Americans. Why not, the high command had concluded, gather up every husky and savage wolf-hound in America? Why not train these beasts in the art of ripping to pieces every Jap they met Why not leave it to the perceptive canine sense to differentiate between Japs and Anglos? (145)

By June 30, 1946, the entire War Relocation Authority program was to be scrapped and liquidated. In essence, it was official pronouncement to the Japanese that soon they would be free to go home. But with their homes gone, their businesses vanished, with families divided and destroyed, every internee knew that the going home was likely to be a hell of a lot worse than the going away. (168)

But camp suicides seemed never to be prompted by war's death loss, or among those who had given husbands and sons to the nation's military. Preponderance of those who chose total immolation, or who were rescued in the attempt, seemed to be the Isseis who had openly or covertly resisted the war efforts.

To these people self-destruction was the final and honorable way out. To open one's wrists, and watch the blood of life pulse away—to weakness, insensibility, and then merciful oblivion—was not a particularly difficult way to die. In the camps this form of immolation was not uncommon. Tule Lake surpassed Poston in the number of suicides. (195-6)

There was little doubt in the minds of some Poston residents that those evacuees returning to California were in for rude awakening. There was no question about the sensibility and adaptability of their people. The frightening thing was that not even the unmatched patriotism of the Japanese Americans was sufficient to offset the avarice of those who had profited at their expense, or the militance of the opposition arrayed against them. One had only to read the fresh alarms out of the newspapers and radio to realize that resettlement was apt to be as hard and harsh as the evacuation. California once more was aroused, and that state's antipathy toward return of its "Japs" was blatant and vicious. The Native Daughters of the Golden West had already sped their resolution to the State and Federal governments. "Immediate exchange of people of Japanese ancestry in this country for American prisoners of war held by Japan," it demanded. "No return of evacuees to the Pacific Coast area." (198-9)

For months the citizenry of California had been well supplied with stickers for walls and car bumpers reading "NO JAPS IN CALIFORNIA." Patriotic societies seemed to have ample funds in their war chests to underwrite the costs not only of public blasts, but for public and private lobbying. (199)

The American Legion, at its convention held in San Francisco, spoke eloquently out against the Japanese blight. With the eyes of a seer, and with voice of thunder, its Department Commander, Leon Happell, trumpeted: "We must look at this problem as of 100 years from now, when 150,000 Japanese will have multiplied and multiplied. This is not the time to take the Japanese out of the camps ... !" (201)

Amid this climate of hysterical resistance, it seemed quite proper that the American Legion Post, at Hood River, Oregon, on December 14, 1944, should erase from their county war memorial the names of sixteen Americans of Japanese ancestry, at the very moment serving their country on the European battlefield. (202-3)

|